BAFA © 2010. All material here is copyrighted. See conditions above. |

Reviewed by Sonja van Kerkhoff

The Netherlands.

|

One of the Overview of the exhibition "Who Am I? Belief and Identity in Art", 2000

Black and White photographs by

Fiona Pardington and Laurence Aberhart, and the painting "Venus and

Re-entry: The Bleeding Heart of Jesus is seen above Ahipara", by Colin McCahon on the right.

|

Miracles of vision

Review of the exhibtion, "Who Am I? Belief and Identity in Art"

at the Sarjeant Gallery,

W(h)anganui, New Zealand.

This is a show about belief, but it does not present belief as synonymous with the singular vision. The 12 themes spread in the 12 bays are not ‘Stations of the Cross’ - are not articulated as one story. The thematic areas are more like organic demarcations. Some assemblages are the results of workshops such as the workshop on devotion given by the Cuban visiting artist, Ana Flores. Here, an old hollowed out tree trunk, reminiscent of a pier or vessel, has been laid across two plinths. It is filled with what seem to be relics or offerings made by those in the workshop. A white cloth was pulled towards the ceiling from the middle of this like a covering for the precious cargo, or a sail. Offerings of ribbons, texts and papers were sewn into the cloth and piles of stones and sticks had been stacked in each corner of the bay. The vessel had a strong sculptural form, and on close inspection is also a receptacle for many small well-crafted evocative objects.

|

The way themes flow in and through the 12 arrangements is the strength of this densely packed show. Rayner has managed to avoid stereotyping belief

- or identity, for that matter.

At the end of one wing McCahon's mystical work, "Venus and

Re-entry: The Bleeding Heart of Jesus is seen above Ahipara" is flanked on one side by the results of artist-in-residence Jeff Thomson's workshop on the self with high school students and on the other side by black and white photographs by Fiona Pardington and Laurence Aberhart. The McCahon is given hommage and rightly so. It glows and resonates, yet the adjacent works pull away from the iconic in subtle ways. The self portraits by Thomson and others are raw and direct, physically pushing out into the spaces around. On the other side the Pardington photographs of found objects with religious and Maori associations raise questions about our colonial landscape of debris.

|

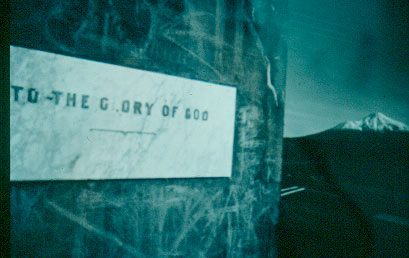

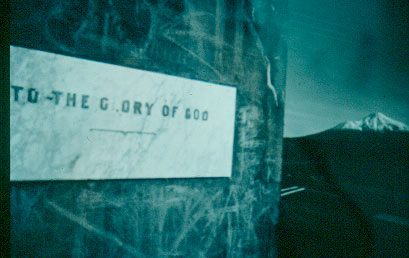

The Aberhart photographs are closer to McCahon in sensibility but like the other works are intimately connected to the concrete world. In one photo the words, "Glory to God" seem to shout out of the stone they are embedded in while the majestic Mount Taranaki backdrop anchors the eye. With simplicity both tombstone and mountain are shown as markers in the land.

Next to the photographs, Matt Hunt's figurine arrangements on about 30 tiny shelves turns all this hommaging on its head.

|

"To the Glory of God" photograph by Laurence Aberhart.

|

Small handwritten scripts tell of aliens, of takeover by a false prophet with 6 fingers.

It is raw, colourful and funny.

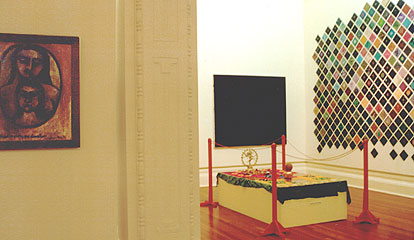

Rayner's inspiration to develop the show began while interviewing the Wanganui abstract painter, Prakash Patel. He realised that belief informed Patel's secular-looking work. In this show Patel's abstract paintings are arranged around a rangoli altarpiece, next to a bay celebrating Catholicism. It could be tempting to present two such themes as examples of the ritualistic but this has not been done.

|

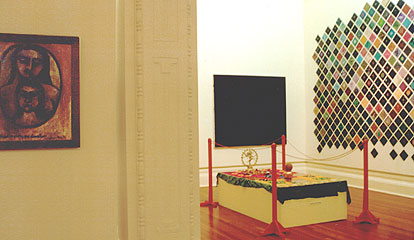

Left to Right: "There is only one direction (Mary and Jesus)", by Colin McCahon,

Hindu altarpiece and paintings by Prakash Patel. |

The colourful Hindu altarpiece works as both counterpoint and compliment to the dark abstract paintings while the Ann Noble photographs of nuns document with sensitivity, the devotional and intimate. On the borderline between these two areas is another McCahon, the 1952, "There is only one direction (Mary and Jesus)" of a monotone Madonna and child, flanked by the words of the title. The words at first glance point to a singular and certain vision. But the image is not a Christian statement of affirmation in the 'sacred art' tradition.

|

The Holy pair, and particularly the volumes of the child's face, are earthy. The child stares out, and I think, "This is MacCahon looking, telling us there is only one way forward." Does it mean all directions are really one? The figures are solid, directed. Perhaps the point is what might have been said, and is not., "there is only one way." "I am the direction, the truth and the life?" The destination makes the identity.

|

Across from the McCahon, a huge teardrop shaped form by Marie Smuts-Kennedy hangs from the ceiling. Numerous hands emerge out of it, reminescent of those multi-handed deities. Next to this, a Pauline Thompson pastel of clouds in an estranged landscape. The McCahon is located on an intersection: the concept of a singular vision is one religious container alongside others.

It certainly was a densely packed show. Some bays might have worked better with fewer works, yet the diverse juxtapositions worked so well because of the close proximities. The wildly coloured epressionist Philip Clairmont painting, "Bhudda: Vietnam" was set off by the large Buddhist drum and gongs placed right next to it.

|

Sculpture with sound by Marie Smuts-Kennedy hangs from the ceiling.

|

A crowd of ninety-nine 10 inch salmon pink cloned Christs by Rebecca Pilcher looked great packed into the niche around the dome area. The David Sarich icon-like Christ painting -this time with a ladder, seemed to converse with the photographs of Ratana Temples on each side of it.

In another bay the words on a panel "No hea Koe?" reminded me that responding to the questions, Who Are You? Where are you from? has many ramifications from a Maori viewpoint. A series of photos show the work of Ngati Mahuta/Upokorehe carver, Dean Flavin for his home whare whakairo (Tribal Meeting House on the East Coast of the North Island). The emphasis here was on community identity in a carving project spanning seven years.

|

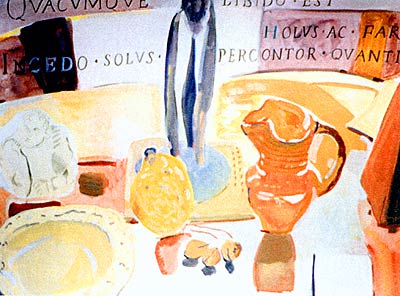

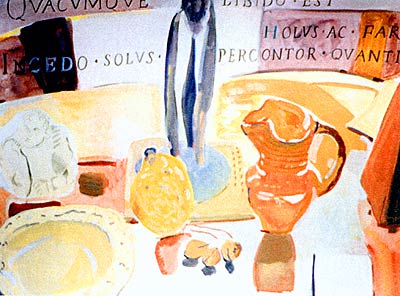

One of the Frugal Pleasures series, 2000 painting by Joanna Paul, New Zealand.

|

Across from this was an album of photographs showing Tibetan Buddhist monks building an installation, with input from members of local W(h)anganui Maori tribes, in the Sarjeant Gallery dome a few years ago.

Around the corner this theme flowed into works where letters and words dominate. Joanna Margaret Paul's "Frugal Pleasures" juxtaposed Latin text with still life watercoloured liquid forms. The whiteness of the table cloth is her altar and her world and the fruits and words are both reminders of contemplative asceticism and layered reflexivity. In Peter Ireland's painted samplers of the spirit, letters hover over darkened romantic landscapes.

|

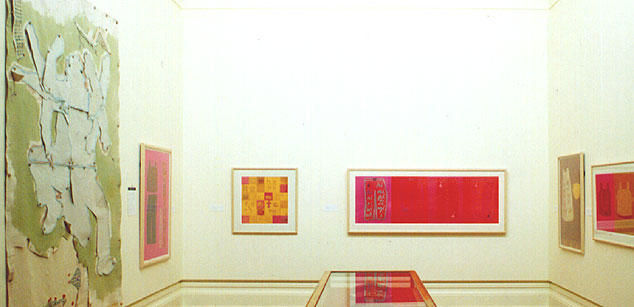

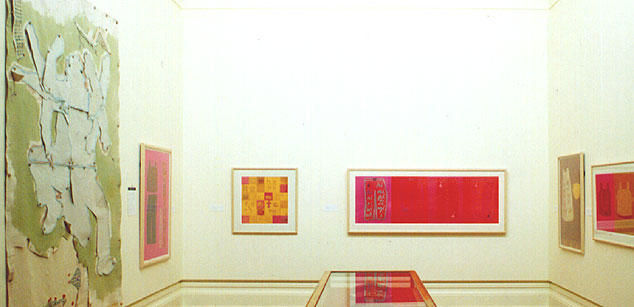

Further on Faith McManus has married letters to the clothes we wear. The garments, with their fold-over tags, are flattened by even colour. They assume a lively physicality when the imbedded words are recognized as a song taught in learning Maori, which immediately remind us of our postcolonial world. The clothing is made to fit over flat toys, and a suppressed language is relearnt. The vivid clothing is teaching us something too, about celebration and the mutability of appearance. The formalism in the adjacent Philip Trusttrum canvas garment-like cut-outs in "Button Down", seem to be given a context by the McManus works.

Left to Right: "Button Down" by Phillip Trusttrum and the silkscreen series by Faith McManus.

|

| Finally, there is a huge crucifix form by Rebecca Pilcher. It is made out of 68 bars of virginal white soap and hangs above a porcelain sink. This could be an altar and yet is not an altar. The work is surrealist in its playful use of material and association. The soap could be like bits of a puzzle. We wash daily, perhaps we should pray daily? Is washing prayer? Or, does the cross dissolve, like soap? Yet this 'altarpiece' is an ordinary sink, so the cross looms over me as I mentally wash. On rising, my reflection is replaced and absorbed by the soft rounded forms. I see a cross or I see soap instead of the

expected mirrored self. It's a piece about the everyday after all, and yet...

no day is just the everyday. There is only one direction then, from where we are to something more, to the transcendence immanent in the now. And tomorrow will be the same, but not as this is.

(This is a reference to the well-known McCahon painting bearing the text:

'And tomorrow will be the same, but not as this is.')

This is an edited version of a review that appeared in Art NZ, January 2001.

Excerpts from Arts Dialogue, June 2001.

|

Arts Dialogue, Dintel 20, NL 7333 MC, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands

email: bafa@bahai-library.com

|

|