|

|

Abstract:

An account of the Bahá'í Cause in Japan, China, Korea, and the Hawaiian Islands, prepared by request of the Guardian.

Crossreferences:

|

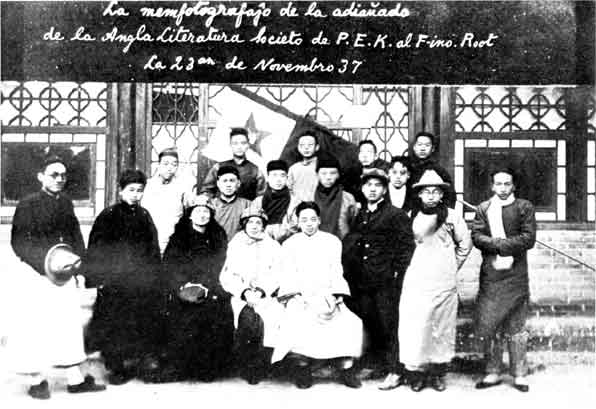

Chapter 5Meeting the Editor of the "Canton Times" In December, 1919, ‘Abdu'l-Bahá said to some American pilgrims in Haifa, "New China has just awakened." One morning in the summer of 1920, I read in the newspaper that a group of Chinese newspaper men were visiting Tokyo. Immediately a burning desire came in my heart to tell them of the Bahá'í Message before they returned to China. When Yuri Mochizuki, who lived with me, came home from the newspaper office where she worked, I asked her if she had heard of the visitor. She replied that they had visited the newspaper office but she did not know where they were staying. The next morning, as I knew of no other way to find them, I turned to the Beloved and supplicated His assistance. While in prayer the name of a Japanese friend, a clerk in the Imperial hotel, came to me. I went right to the hotel and asked him if he could tell me where to find the visitors. To my surprise he replied that he had not heard of them, then suddenly he said, "Call up the Chinese Legation and ask them." As I did not succeed in telephoning, I decided to go to the Legation myself. At the Legation entrance I met the gatekeeper and told him my errand. He escorted me to the office and I procured the name of the Inn where the group was staying, but learned they were away for the day, and would remain only two days longer in Tokyo. The gatekeeper, who was of Chinese-Japanese parentage, and spoke English fluently, seemed delighted when I told him of the Bahá'í Cause and gave him some booklets. Indeed, it was the wonderful guidance of the Master which led me to the Legation, and the contact I made there opened the way later for me to meet a secretary who became very friendly to the Cause, and was one of those who spoke at the memorial meeting for the Beloved Master. The next morning, with Yuri San's help, I telephoned to the Inn and asked to speak with someone of the group who understood English. To the one who came to the telephone I gave my name and address and asked him to come and see me. Later in the morning he arrived. He looked very uninterested, but as soon as he heard of the Bahá'í teachings, his whole expression began to change, until when he left his face was radiant. Mrs. Finch had a supply of Bahá'í books to sell, and he procured all available books to take with him to Canton, where he was an editor of the Canton Times, a leading newspaper of China. The following morning he returned accompanied by a friend, Mr. S.J. Paul Pao, of Shanghi, whom he had told of the Bahá'í teachings. Mr. Pao was delighted to hear of the Cause and over and over again repeated, "Wonderful teachings! Wonderful teachings!" I gave the Canton editor a photograph of ‘Abdu'l-Bahá and asked him if he would publish an article in his paper when he returned to Canton. To my great delight, after his return, he sent us a copy of the Canton Times in which the photograph of ‘Abdu'l-Bahá appeared on the front page with translations of Words of Bahá'u'lláh and ‘Abdu'l-Bahá. The translations continued to be published in twenty-five editions of the paper, which he sent to us. As the Canton Times was widely circulated in China, the knowledge of the Bahá'í Cause was spread far and wide throughout the country. A proof of this came later when I had occasion to visit the Chinese Legation and inquired if the Minister had heard of the Cause, and was told he had read of it in the Canton Times. At another time I asked a Chinese student if he would send something to be published in the newspaper in the northern province of China where his home was. He told me afterwards that he received a reply that they had already read of the Bahá'í teachings in the Canton Times. After Mr. Pao's return to Shanghai we corresponded for a while, and George Latimer also exchanged letters with him, then he moved and I had no way of reaching him. In Shanghai a Mr. P.W. Chen was in his office one day and saw some Bahá'í literature on the table. Mr. Pao requested him to take it and translate it for a Shanghai newspaper, which he gladly did. When in Peiping, in 1923, with Martha Root, we met Mr. P.W. Chen, and through him found Mr. Pao who was then living in Peiping. This was the beginning of the Bahá'í Message reaching China through Japan. Thus before the passing of ‘Abdu'l-Bahá it had become known in China, and from that time other doors opened in Tokyo to give the Message to Chinese students. In February, 1922, a young lady who had come from Honolulu, came to stay with me. On the steamer she met a Chinese officer of the Aviation Corps of the Chinese Army, who was returning to China from study in the West. Through her I met him and gave him a Bahá'í booklet containing the Bahá'í principles and invited him to come to our Bahá'í gathering that afternoon. When he arrived in the afternoon, after having read the booklet, he expressed great enthusiasm for the Bahá'í teachings. Ten were present in our meeting that day, representing China, Korea, Japan and America. Lieut. K. Tsiang wrote in my guest book, "I am so glad to hear the explanations of the principles of Bahá. . ." When Martha Root and I were in Peiping, the next year, we met him and he invited us to speak to the men who were under him in the aviation training school, many of whom were army officers. Among the friends whom I met when in Korea in 1921, was a young man of Korean parentage who was born in China. Later he moved to Tokyo where he asked me if I would teach Esperanto to a group of Chinese students at the Chinese YMCA. I felt it was an opportunity to spread the Cause and gladly accepted. There were sixteen in the class, only three of whom understood English. Their text book was in Japanese and I was asked to teach Esperanto conversation. One of the students, Mr. H.C. Waung, acted as interpreter. I wrote on April 11, 1922, to a friend: ". . . pray that some of these souls who have pure hearts may find His love. We can teach them without words." After a few lessons I told them briefly of the Bahá'í Cause, and wrote on the blackboard the names of the Revelators and ‘Abdu'l-Bahá On May 6, 1922, we held a special meeting for Chinese students to make known to them the Bahá'í Message. Six came and the brother Mr. Fukuda. Again on May seventeenth, we had hoped to have a feast for Chinese students, but only one was able to come, Mr. H.C Waung. In my guest book I wrote after his name: "May this seed grow and enlighten many!" On December twenty-second I added the words: "Mr. Waung has translated the booklet, 9, into Chinese and it is now published and sent throughout China." That summer Martha Root had written me asking if I could have the booklet, which contained the Bahá'í principles and extracts from the Holy Writings, translated into Chinese. Mr. Waung was then on a visit in China, and I wrote him and asked if he could do the translating. He answered me that a feeling came to him of something which would come in the future, and working steadily, in three days he was able to accomplish the translation. Dr. Y.S. Tsao and other Chinese friends commended it as a very good translation. It was published in booklet form and afterwards was reprinted in several editions and thousands of copies were distributed throughout China. How great was the blessing which came through the Esperanto class! Chinese Students Visit Japan On May 4, 1919, after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, the Chinese students arose as one body against the decision in regard to their country. From that day there commenced a new movement called the Student Movement, which took hold of and inspired the youth of China, and from one end of the country to the other they organized. A steady tide of social and educational reforms together with the discarding of the traditions of the past advanced with bounds. It was the outward sign of the onward march of a "tide of new thought," as it was called in China, and new life currents burst forth pulsating with intense vigour the student world. The eagerness for knowledge of these students, brought to Japan during May and June of 1922, five groups of students from Higher Normal Schools to inspect the schools of Japan. The groups came independent of each other, each group being sent by the local government of its province. A sign of the awakening of the youth of China was that in the past only two such student groups had visited Japan, and also that one of the groups was composed of young women, the first Chinese young women to be sent from China on such a mission. Just as ‘Abdu'l-Bahá sent His Divine Plan to the five points of America, so also the student groups came from the five points of China, that is, the North, South, East, West and Center. The morning of May eighteenth, a picture of nineteen Chinese young women from Peiping Women's Teachers College, appeared in the daily paper with the statement that they were to be guests of honor that evening at a dinner given by a Japanese newspaper. It was the paper where Yuri Mochizuki had worked before she went to France. In my eagerness to meet the girls and tell them of the Bahá'í Cause, I went to the newspaper office and asked if I might attend the dinner, and received an invitation. Besides the guests of honor at the dinner, and the representatives of the newspaper, some Japanese young women teachers were present. The after dinner speeches were in Japanese into which those of the Chinese girls were translated. After the dinner I met two of the Chinese girls and arranged to call on them. The next morning, May nineteenth, a new joy and inspiration came to me about China, that I would go there myself. The words of ‘Abdu'l-Bahá regarding the teacher of the Chinese people rang in my ears: "The Bahá'í teacher of the Chinese people must be imbued with their spirit, know their sacred literature, study their national customs and speak to them from their own standpoint and their terminologies . . ." I immediately went to ask a friend where I could procure books on China. A wonderful opportunity opened to me to study in a library made up of books about China, which had been brought from China to Japan. The books were being catalogued and I was given freedom to read any I wished. The dinner speeches of the Chinese girls appeared in the Japanese newspaper which sponsored the banquet. The speech of one of the girls, Miss Chien Yung Ho, to whom I was particularly attracted, was translated to me. She said that the Chinese Women's Association of Peiping wished to give all people a chance to live, and especially the lowest class, that all mankind should be allowed happiness without the limitation of sex, race or country. She said they had lost interest in politicians and were developing their interest in world ideas; that they wished to do their utmost for the happiness of the whole population without respect to religion or race, and that their future aim was to establish correspondence with the women of the world. I went to see the Chinese girls who spoke English and told them my joyful news, that I would go to their country sometime, and gave them some Bahá'í literature. They remained for two weeks in Tokyo and several times I met with them. They told me how within a year all the schools of China, from the grammar to the University, had been opened to women for the first time. The Bahá'í principles of universal education and equality of the sexes were then taking root in China, although Bahá'í teachers had not visited that vast Empire. The last time I met the girls was at the station when they were leaving Tokyo. Miss Chien, the girl whose speech I have quoted, put her arms around me and said, "You are my teacher." She invited me, when I would come to China, to visit the school where she was going to teach and tell the pupils about the Bahá'í Teachings. A year and a half passed and this was fulfilled when Martha Root and I traveled together in China in 1923. One evening when I went to see the Chinese girls, in the hall I saw some Chinese young men who greatly attracted me. They were from the second group of Higher Normal students who came from China to visit Japan that year, and were from the geographical center of China, the city of Wuchang. Through the Chinese girls I met and talked with some of the group which was composed of thirty-four students. One of the group expressed their ideas as follows: "We love peace, that is our spirit. As we are the oldest civilized country now existent on the earth, our sacred books are many, but the essentials are 'Four Books' and 'Five Classics' of Confucius. We emphasize moral education more than knowledge, but knowledge is power and we do not neglect it. There came a turning point in 1919, which is The next group of Higher Normal students from China to arrive in Japan were from Peiping. A member of the Chinese Esperanto class, who was attracted to the Cause, arranged for me to meet one of the group on June twelfth. I first questioned him and took notes of what he said before telling him of the Bahá'í Teachings. He said: "We have doubts about everything. We believe we should be active but not blindly. We want information, and are so eager for it we have come to Japan, although we don't know whether we can get anything. We all know that the Peiping government is as corrupt as possible, but this very corruption awakens us. The present condition may seem rather pessimistic, but the students are a force without arms which is known to everyone and their power is feared. The government on one hand tries to suppress them, but on the other hand pays them respect. In the government in Canton women have demanded the privilege to sit in parliament. Woman's emancipation is not only advocated by women, but by men. Many new magazines have appeared especially dealing with this question. Two years ago new schools for women were started throughout the country and within a year coeducation has been adopted in all the government schools. Women are now admitted to the Peiping University. Now young men and women meet together freely. It is the women who will bring the emancipation of the race. They are the other half which is springing up. The greatest cooperation is that between the males and females. At first the social intercourse between the sexes seemed to shock the common people, but now they have become accustomed to it. The aims of the students are first, sound government; second, real liberty; third, peace which we always love and advocate. If these things are realized, the students can then devote themselves to study and contribute to the world's civilization, which is their fourth aim. These things are the good side, but we have to pay for them. The farmers are not able to raise their crops only because of civil wars. Though coeducation is enforced we have drawbacks. First the students, male and female must have sufficient knowledge, or they make blunders. If on the one hand they have not enough knowledge, the wrong will be committed. We have little knowledge of foreign affairs but we have doubts. All such things are compensated for by what we have received. There is a new movement which commenced on March ninth of this year. It is so called the 'Anti-Religion Movement.' It has sprung from the doubts. We want emancipation and liberty. We feel religion is something which binds us. This movement is now very strong. It was first organized in the schools in Peiping and now has spread to other places forming a unit. The base of the movement is science. It is to break away from all superstitions. Religion is superstition which is against science. The movement started against Christianity. Christianity itself is all right, but it is the conduct of it and its abuses which the movement is against. The scholars have not yet paid great attention and study in regard to this movement. They have not yet expressed their opinions. If they did it would be solved. We wait for the great scholars. We have now no proper solutions. We wait for results. "The impression from our visit to Japan is that the Japanese are certainly more advanced in education than we are. They have a spirit of doing. If they get a new idea, they try to carry it out and they have favorable conditions. In China this spirit is not so strong because we are now discussing and have not yet reached conclusions. In this way the Japanese educational work is better than ours. The Japanese are faithful, not only to their nation as a whole, but to their profession. Another thing is they have order. At present the Chinese condition is quite different, there is no order at all. A proverb of Confucius says that if you are in a dilemma which way to go, you will never reach your destination." When the student finished speaking, I told him of Bahá'u'lláh and the Bahá'í Message which he was ready to understand. In Peiping I met this young man again in 1923. Another group of fifty Higher Normal School graduates arrived in Tokyo from the far western city of Chengtu in Szechuan province. My longing to meet them was so great that until it was achieved I could not rest. The good friend, Mr. H.C. Waung, assisted me to meet four of the group, whom he guided to my home and gave me the opportunity to tell them of the glorious Message of Bahá'u'lláh. They told me how they had traveled for a month to reach Tokyo. The first twelve days were through rough country in sedan chairs, then by river steamers until Shanghai was reached, where they embarked for Japan. One of the students said that the people of their province were ready now to do anything which would be for the good of the people. He said: "All countries are now searching education. In our educational work we have two problems. The first is financial. We have not enough money and this is due to the government. The other problem is that many of the old school people hesitate in adopting new ideas and because of the isolation of Szechuan province, education is difficult. Of course China is now in a very confused condition, but it is a necessary step we have to take. Our characteristic is peace. Our history is more than four thousand years old. Three thousand years ago Emperor Yu realized that a country should have an aim, and he made the virtue of the people the aim. From that time until the present we have held this aim. We have not invaded other nations, although the Chinese people have been humbled by other races. All Chinese love peace and realize that friendship among countries is necessary. We have never prepared to attack other races. . . . I am quite sure your doctrine will be welcomed everywhere in China, for as I said, the people love peace and they want to unite the world as one." After their return to China, when the students became teachers in school, I corresponded with two of them. One of these, Kai Tai Chen, wrote an article for me which was published in the Bahá'í Magazine (See Vol. 13, page 215). The other student, Mr. T. Z. Wu, became a teacher in the Middle School in Nanking, where in 1923 he invited Martha Root and me to speak to the school. The last group of Chinese Higher Normal graduates to visit Tokyo were a party of twenty-two who came from Canton. While in Tokyo their time was filled, and only through the help of Mr. Waung was I enabled to meet a member of the group, but as ‘Abdu'l-Bahá said, one holy soul was better than a thousand, so this young man, Shik Fan Fong, became illumined with the Message of Bahá'u'lláh. Mr. Waung told him of the Cause and arranged to bring him to my home. The day on How great was the bounty of God which assisted me to give His Message to representatives of these five groups of Chinese students! None of them had heard of the Cause before, yet their thoughts were permeated with the very principles which Bahá'u'lláh gave to the world. It was an inspiration to meet them and feel them and feel the new life which was pulsating in the heart of young China. The seeds sown in these awakened students blossomed in China, where some of them assisted Martha Root and me in 1923 to give the Bahá'í Message to their pupils. After they left Tokyo, in the hot summer, while others were vacationing, I had the great privilege of spending many hours reading in the library of Chinese books, preparing for the time when I too would go to China. Letters From Chinese Students After the Chinese student groups returned to China, I corresponded with some of them. In a letter to me, Miss Chien Yang Ho wrote: "Traveling to Japan gave us the good luck to meet you, who accepted us with your very warm heart. . . Our schoolmates recently have a conference called, 'Female Freedom Extending Conference.' The purpose of it was to discuss and settle things regarding education, constitution, economics, labor, etc., with respect to females. The meeting will be held weekly and famous people are invited to give lectures and magazines are to be published . . . Besides this conference, a Women's Suffrage Conference has been established by the Peiping girls. . . I would appreciate it very much if you let me have ‘Abdu'l-Bahá's writings. . . . All of us are remembering you and desiring to hear from you at all times. Your loving friend." Shik Fan Fong, the student from Canton, wrote me: ". . . Cantonese have actually the world spirit and ideas of this age for we received the foreign people first of all the places in China, and also a great many of us have traveled about the earth. We had tried to modernize our city to an ideal one, especially the last few years, the returned students from foreign countries make much more progress. We like peace much, and we like universal peace still much more. Therefore the principles of ‘Abdu'l-Bahá will be surely welcomed with heart and soul in Canton. So far as I have returned to Canton many of my friends have come to see me and asked me what I had gotten from Japan. I always named out firstly you, the universal teacher, and Bahá'u'lláh, the beloved Master. In fact, you are the most figurative feature in my record of this journey. I have tried to convey His Message of Truth to my friends whenever and wherever I have met with them and they have been heartedly welcomed. After I have studied all the pamphlets and paper you gave me, I shall translate some of them into Chinese. . . I will be very glad to hear from you the lovable Truth, and I hope to do my best for the truth!" In another letter from Shik Fan Fong, written on the steamer on his way to California to enter the University there, he wrote: "In order to know that you will come with honor to our China, I am very glad to welcome you with heart and soul for you are the Messenger of God and you come really for the welfare of China and for the good of this age. One thing I have to inform you is that the universal language has been set as a course of study in our college beginning this autumn. Indeed, many magazines, newspapers and educators have encouraged the teaching of Esperanto in Chinese schools. This may be a good chance for the spread of the new spirit of this age to China, for the universal language may be as the wire to the telegraph or the ether to the wireless." Again from Berkeley, California, where he entered the University, Shik Fan Fong wrote: "Some of my friends here after listening to what I said about this revelation, became interested in research of the history and development of the Bahá'í movement. Among them, a close friend, . . . intends to know more about the religion. Many thanks if you can help him. I have a thousand good wishes for your coming glorious deed as Messenger to our China. Accept them as a remembrance of Bahá'í Brothership." Mr. Wu Tun Zin, who came to Tokyo with the students from Szechuan, wrote me in April, 1923: "I am very glad to know that Miss Martha Root will come to China for the sake of spreading the Glad-Tidings of the Bahá'í . . . I am very glad to hear that you are so interested in China. But I think it would be much better for you to come to China and study it in a direct way, for I am afraid the information from books which are often described as 'secondhand' is not always reliable. . . After all, I should think that if there were a Bahá'í Assembly somewhere in China, things would go on smoothly. You could publish articles through it and adopt any means you might think effective for the spreading of the great movement. I think Miss Root must have thought of this when she comes to China." A letter reached me in Tokyo on September 20, from the Greatest Holy Leaf who wrote: Haifa, Palestine you a pioneer in carrying the Message of this Dispensation to the farther most countries of the world and to the most obscure. In China With Martha Root in 1923 At the time of the great earthquake of September 1, 1923, in Tokyo, my own sister, Miss Mary C. Alexander was climbing Mt. Fuji and it was a month before she could return to join me again in Tokyo. Then I disposed of my household belongings, and on October twelfth we left Yokohama by steamer. On the way to Peiping by train, we stopped for a few days at Seoul, Korea. Beloved Martha Root was in Peiping looking forward to our joining her there, which the great earthquake brought about. As we left Japan everything was orderly but on arrival in Peiping it was the reverse, due to the economic conditions and the struggle for existence of the poor. Before we reached Peiping, Martha had gone one day to Tsing Hua University, formerly the Boxer Indemnity College of Peiping, and called on President and Mrs. Y.S. Tsao, who received her most kindly. Her errand was to speak to them of the Bahá'í Cause which they listened to without prejudice. This little act of Martha's was productive of great confirmations and far reaching results. Mrs. Tsao was of Swedish birth, but became a naturalized American. She was a truth seeker and member of the Theosophical Society. Dr. Tsao graduated from Yale College in 1911. He was married in London where for five years he served his government. When he reached Peiping, through Martha, Dr. Tsao had invited me to speak on the Bahá'í Cause in the University auditorium before all the assembled students. Dr. and Mrs. Tsao also entertained us at a Chinese luncheon. Then he arranged for a second meeting, inviting any of the students who wished to talk personally with us. Four earnest students gathered, each one having a different problem. One had been brought up as a Muhammadan, another as a Christian and a third had no religion. I was a very stimulating meeting, as each spoke from the depths of his heart. From that time Dr. Tsao allied himself with the Bahá'í Faith both in writing and in public speeches. In Peiping I met again Lieut. K. Tsing, who had heard of the Cause when passing through Japan, in my home in Tokyo. He was in charge of an aviation training school and invited Martha and me to speak there on the Bahá'í Cause. The school was composed principally of adult men, many of whom were army officers. It was an inspiring experience to speak to these men of the Promised One of this age. Lieut. Tsing spoke first in Chinese most earnestly, and then introduced us and interpreted our words into Chinese. The men were most attentive and appeared to be without prejudice. At another time Lieut. Tsing entertained us for dinner. One day in Peiping Martha went to a meeting where she had an opportunity to mention the Cause. After the meeting a Mr. P.W. Chen came to her and asked if she knew Mr. Pao. He was the friend who had visited my home in Tokyo in 1920, with the editor from the Canton Times and heard of the Cause. It was a great joy to find that he was then living in Peiping and serving as one of the secretaries to General Feng, known at that time as the Christian General of China. He came to see me and it was arranged for Martha and me to speak at General Feng's school, which was attended by the children of the officers in his army. It was a very happy occasion and every child in the school was given a Chinese Bahá'í booklet, thus they became torch bearers of the Message of Bahá'u'lláh to General Feng's army of 10,000 men. From the day Martha met Mr. P.W. Chen, he became a devoted friend and assisted us. It was he who saw the Bahá'í books which Mr. Pao had brought from Japan, in Shanghai in 1920, and at Mr. Pao's request translated from them for a newspaper in Shanghai. In Peiping he was a teacher of a middle school. Through him Martha and I were invited to speak in a large gathering on the Cause. He introduced us to a Mr. Deng Chieh-Ming, who became an ardent friend to the Cause. At that time in Peiping there was an Esperanto School where Martha was assisting in teaching English. On several occasions we had gatherings there and spoke of the Cause. With Mr. Pao's assistance we arranged on November fourth to hold a Bahá'í feast, the first of its kind to be held in Peiping. Seven friends were present including Mr. Pao and Mr. P.W. Chen. The month spent in Peiping was filled with Bahá'í activities. There we met Dr. Gilbert Reid, editor of the International Journal. He had the distinction of being the only person in China, as far as we know, to receive a Tablet from ‘Abdu'l-Bahá. His spiritual eyes, though, were not opened. When we left Peiping, we stopped at six cities on our way to Shanghai. In two of these cities there were teachers whom I had met in Tokyo when they visited there after their graduation from Higher Normal Schools in China, and in a third city there was an Esperantist with whom I had been corresponding. These friends had invited us to come to their cities and speak of the Bahá'í Cause. In the other three cities we visited, we had introductions from friends in Peiping to teachers of schools where we had opportunities to speak of the Cause. Martha and I carried with us wherever we went several hundred of the Chinese Bahá'í booklets, which had been translated by Mr. C.W. Waung, the student in Tokyo. These we distributed in all the schools where we spoke of the Cause, and through the pupils they would reach the homes, and thus the Word of God for this Day was scattered far and wide in our travels in China. The new friend, Mr. Deng Chieh-Ming was so eager to learn all he could of the Cause, that he accompanied us on the train to Tientsin, our first stop. There we spent a night and Martha spoke in two schools. At midnight we took a train to Ginanfu, the city where my Esperantist friend was a student. It happened to be a Chinese train which had a special compartment for women. When the Chinese women in the compartment saw us entering they were frightened. Then the kind friend, Mr. Deng, who had accompanied us, explained to them who we were and that we were friends, which put them at ease. My sister had preceded us to Ginanfu, but on account of Martha's talks we could not leave, and were obliged to take the late train. On the way to Nanking, Martha and I dropped off the train at Tsuchowfu, where Miss Chien Yung Ho, whom I met in Tokyo from the Peiping Teacher's College, had become principal of a school. She had invited us to stop there and tell her pupils of the Bahá'í Cause. We had expected to let her know when we would arrive. As it happened we did not know in time, and our message reached her only after we had arrived. It was very early on a cold morning that our train reached Tsuchowfu. Just as Martha and I stepped from the train, two American men were boarding it and asked where we were going. We found that the Chinese city of Tsuchowfu was distant from the railroad stop. They had come to the train in rickshaws and told us to take them and go to the house they had just left where a warm fire was burning. We were certainly protected and cared for by the Hand of God. The owner of the house where we were taken was an American who was in the Standard Oil business and was accustomed to taking in guests. When we told him of the school we wished to visit, he offered to go with us to the Chinese city, several miles distant, and inquire at the American Mission hospital where to find it. The school was near the hospital, and within an hour after our unexpected arrival, we were telling the Glad Tidings to the pupils in that far away school. Then Miss Chien and other teachers arranged a gathering for us in the afternoon and we remained with them until evening, when we returned to the home of our kind host, and left early the next morning on our way to Nanking, where we again joined my sister. In Nanking was Mr. T.Z. Wu, whom I had met in Tokyo with the student group from Szechuan. He was teaching in a middle school and through him we were invited to speak to the students. We also spoke in several other schools and in all the schools, the teachers of English acted as our interpreters. From Nanking we went to Soochow where again Martha spoke in many schools. When we reached Shanghai, our last stop, Martha was not well for a time, and was obliged to rest. Afterwards she visited other cities in China, as Wuchang, Hanchow, Canton and Hongkong, everywhere actively working day and night to spread His Message. The Esperanto student, Daniel Yu, in Ginanfu, wrote me on December 6, 1923: "Pro via restado en Tsinan, vi ne devas danki min, sed ni ciuj danku la Providencon, Ke ni havas la sancon prediki la veron en Tsinan. Via semado en Tsinan certe produktos rican rikolton." From the first Middle School of Nanking, Wu Tun Zin wrote, December 24, 1923: "Your life is indeed a strenuous one. I do appreciate your work, still more your spirit. It gives me inspiration in my work, I often ask myself, 'Why don't I have the same spirit in my work, as others have in theirs?' You will be my example, I will imitate you in doing my work, though we are working different lines. After I reached Honolulu, a precious letter came from the Guardian: Haifa, Palestine With Martha Root in Shanghai in 1930 In 1930 Martha Root, who had been in Persia, wrote me that she would be coming to the Far East. As I had felt I should meet her in China, I wrote to ask the Guardian's advice and on April 30, 1930, the following answer came from him: Haifa, March 16, 1930 The latter part of September, 1930, I reached Shanghai. Martha was then in Hong Kong and it was ten days before she arrived to join me. In the meantime I found the dear friends, Dr. and Mr. Y.S. Tsao, who had moved from Peiping, where Dr. Tsao had served eight years as President of Tsing Hua College. The lovely Persian Bahá'í family of Mr. M.H.A. Ouskouli, consisting of his mother-in-law, his oldest daughter and her husband Mr. and Mrs. A.M. Suleimani, his two younger daughters and son, and the Persian brother, Mr. H. Touty were also living in Shanghai. As soon as they and Dr. and Mrs. Tsao came to know one another, they arranged to have Bahá'í meetings every two weeks at the Ouskouli home. When Martha reached Shanghai, Dr. and Mrs. Tsao came immediately to see her, and he offered his services to assist her in any possible way. Then she began her vigorous work, especially with the newspapers, in which she succeeded in getting many Bahá'í articles published. I shall never forget the historic moment when Dr. Tsao voluntarily offered to translate Esslemont's book into Chinese. Martha was so touched that her eyes filled with tears of joy. From that time Dr. Tsao devoted his only leisure time to this work, which was done at night after busy days. In referring to it he wrote: "After studying the Bahá'í Faith and the reviving effect it produces over the heart and mind of man, I came to the conclusion that the only way to regenerate China is to introduce the Bahá'í teachings to China, and therefore I began to translate the Bahá'í books into Chinese, so that the Chinese nation may be benefited too by this heavenly Manifestation. That is why every day after leaving my office, though very tired, I go home and start working on the translations of the Bahá'í teachings, and usually I forget that I am tired." I spent a month in Shanghai and then returned to Tokyo as I felt the urgency of seeing about the Japanese translation of Esslemont's book, which was being done in Tokyo. The story of Martha's wonderful work in China is recorded and will never be lost. Early in 1931, in a letter to me from Dr. Tsao he wrote of his great pleasure in working for: "the Great Cause that is bound to assume gigantic proportions in the future. The signs of the times are pointing so clearly towards it and my Chinese friends with whom I have discussed it at once acknowledge the beauty and importance of it. We pioneers might find it difficult, but when we have more literature prepared, it will multiply our efforts automatically. . . . Since I started the translation of Dr. Esslemont's book, I have had so many outside activities added, such as giving a series of lectures on Scientific Management, to factory managers and staff people, the YMCA campaign for members and funds, lectures on cooperation between employer and employee, Chairman of the Good Road Exhibition to be held in September, and just this morning a request for a paper on 'The Possibilities that Shanghai Affords for Cultural Contacts,' to be read before the Joint Committee of the Shanghai Women's Organization on May 15th. At this last I will stress women's education according to the Bahá'í Teachings, namely, 'the two wings of mankind.' These activities give me the contacts for the Cause we are trying to unfold in China and I feel intensely that with the spirit one's energies are spent, they will be adequately rewarded in the harvest that will be eventually gathered for our common Cause." Miss Fung Ling Liu Visits Tokyo When Keith Ransom-Kehler was with me in Tokyo in July, 1931, we had the joy of meeting Miss Fung-Ling Liu, who was returning to her home in Canton from study in the United States. It was through meeting Martha Root in the University of Michigan that Miss Liu was directed to the Bahá'ís as she traveled westward toward her home. While her steamer was in port in Yokohama, Miss Liu came to Tokyo and spent a night with us. It was an especially happy occasion, as it was the evening when we held a Bahá'í meeting and a spiritual unity was made between this Chinese young woman and the Japanese friends. Miss Liu's brother had accepted the Bahá'í Cause when attending Cornell University, and through meeting his sister, Keith was invited to be a guest in his home in Canton when she was on her way to Australia. Professor R.F. Piper Meets Shanghai Bahá'ís In 1932, Prof. Raymond Frank Piper, of Syracuse University, who had heard of the Bahá'í Cause while in Honolulu, passed through Japan. From China he wrote me on December 5, 1932: "To meet three ardent Bahá'ís in Shanghai the other evening was like a breath of fresh spiritual air from the pure land of God. There were four of us, two Persian, one Chinese and I American. . . . In physical origin we were of three races. I am sure the others, during our happy evening together, were quite as unconscious as I of the difference of racial origins. We realized in profound feeling the unity and comity of mankind. We were one in the spirit of comradeship in the great cause of bringing God and brotherhood to mankind. I wrote in my diary. 'This was a night of joy and illumination.' Mr. Ouskouli wrote in my autograph Dr. Yun-Siang Tsao On February 8, 1937, Dr. Tsao died suddenly of a heart attack while returning to his home from his office in Shanghai. When word reached Shoghi Effendi of his death, he cabled to Mr. Ouskouli, the Persian brother in Shanghai, as follows: Just heard passing dear Dr. Tsao. His distinguished services unforgettable. Assure bereaved relatives friends deepest sympathy prayers. Born in Kiangsu province in 1881, Dr. Tsao was fifty-six years of age at the time of his death. The life of this distinguished son of China is published in the History of the Class of 1911 Yale College which was written by one of his classmates who knew him best. From this history the following quotations are taken. "Yun-siang (Dr. Y.S. Tsao) came to Yale as a result of having proven in his homeland the high quality of his remarkable intellect, for when thousands of Chinese students were vying with each other in examinations for a chance to study in America, Yun-siang, already a graduate of St. John's College, Shanghai, and known for his literary and speaking ability, was offered the opportunity to go without examination and solely because of demonstrated ability. Having matriculated at Yale, he soon gave evidence of his great adaptability to varying situations, a characteristic which has remained prominent throughout his subsequent career and which, doubtless, has contributed greatly to the measure of his achievements." At Yale he won the distinction of being one of the first Chinese students to take part and win honors in oratorical contests. Here he won the de Forest medal, Yale's highest oratorical honor. After graduation from Yale Dr. Tsao studied at Harvard. While there in his activities in the interest of social betterment he became acquainted with another foreign student of Swedish parentage who later in London became his wife. "As he (Dr. Tsao) approached the completion of his university work in America," the History states, "Yunsiang pondered the way in which he could accomplish the greatest amount of good for his countrymen on his return home. Realizing that his viewpoints must have changed considerably in his seven years abroad and that conditions under the new republic would be far different from those which he had previously known, he decided to accept an offer of a position for a year on the faculty of Tsing Hua College, Peking, the American Indemnity College. . . . He had already received attractive offers from prominent business concerns in China but a short while before leaving for home he received a very flattering appointment from his government as a secretary in the London Embassy. After serious consideration, however, he wired back, 'Tsao prefers Tsing Hua'. The government's reply was to bring such pressure to bear on him through friends at home that he was finally induced to accept the post, and he remained in London throughout the war doing such good work that he was appointed Consul-General." In 1919, after serving five years in London, Dr. Tsao returned to China, but before the end of the year his government sent him to Copenhagen as first Secretary of the Chinese Legation of which he became Charge d'Affaires the following year. In 1921 he represented his government at a conference in Geneva and came the same year to America to make the preliminary arrangements in Washington for the Chinese delegates to the Limitation of Armament Conference called by President Harding. Returning home he was made councilor of the State Department and in addition was appointed President of Tsing Hua College, in which, seven years before he had planned to teach. Quoting further the Yale History, "As the College and the foreign office, though both in Peking, were separated by a considerable distance and it was necessary for him to spend part of each day at each place, he felt that he must give up one position and so chose to remain at the College where he had undertaken a considerable program of reorganization. . . . On one occasion while still president of Tsing Hua, he was invited to become the efficiency expert of the largest publishing house in the Far East. . . . In considering the position which eventually he declined, he wrote, 'Personally it makes no difference whether I leave or stay, all I want is to serve where I am most needed and to put my energies where they will tell for society and the country at large,' Always the same unselfish, public-spirited Yun-siang, thinking only of his countryman, never of himself. . . ." The Yale History ends with these words: "He (Dr. Tsao) writes that politically he is a free lance and in regard to church affiliation he is a member of the Bahá'í Movement." While at Tsing Hua, shortly after the Chinese government had abolished the Lunar Calendar, substituting for it the Gregorian Calendar, Dr. Tsao noticed that the Buddhists were celebrating one of their many religious festivals in connection with the Lunar year. He remarked: "Any faith, habit, or habits established by religion can only be altered or changed by religion. Government decrees in such matters will be of no avail." An American lady, Miss Anna Bille, who taught under Dr. Tsao at Tsing Hua University writes: "In my opinion, his biggest piece of work was done at Tsing Hua which he guided through the difficult period of transition when it changed from a junior college, largely American, to a full university, fully Chinese and national, though there were always some American teachers. The plan of development for the new university was careful and sound, and an excellent faculty, with democratic organization was built up. The best equipment was secured and a splendid library had been accumulated. Faculty and students alike found Dr. Tsao an understanding and helpful friend, and all regretted it when he left the university. But so firm were the foundations he had laid that the development which he had planned continued uninterrupted." At the time of his death, Dr. Tsao was the adviser to the Central Bank of China and Editor-in-Chief of the China Quarterly. A seasoned public speaker and a writer who commanded the art of clear diction and forceful presentation, he was an honorary member of the China Society in London and a foreign correspondent of the British Royal Society of Literature. He was also at one time the Secretary-General of the Red Cross Society of China and the China Institute of Scientific Management, as well as President of the American University Club. Besides these offices he was Chairman of the Board of Directors of both the Bosant School for Girls in Shanghai and the Shanghai YMCA and was actively associated with numerous other local organizations. Among the honors which Dr. Tsao received were decorations from the governments of China, Denmark and Poland.  click for larger photo Miss Alexander and Miss Martha Root (center) in Peking, China, 1923.

|

| METADATA | |

| Views | 76853 views since posted 1999; last edit 2025-01-28 14:58 UTC; previous at archive.org.../alexander_history_bahai_japan; URLs changed in 2010, see archive.org.../bahai-library.org |

| Permission | editor |

| History | Scanned 2000 by Jonah Winters; Formatted 2000 by Jonah Winters; Proofread 2000 by Barbara R. Sims. |

| Share | Shortlink: bahai-library.com/409 Citation: ris/409 |

|

|

|

|

Home

search: Author Links |

|