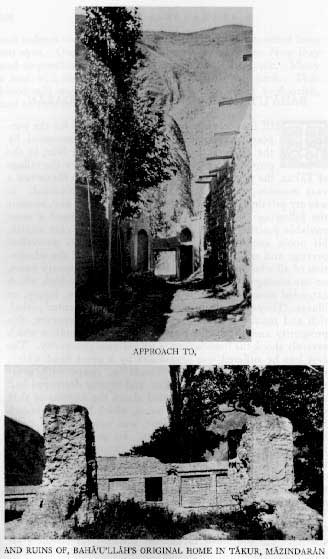

HE first journey Baha'u'llah

undertook for the purpose of promoting the Revelation announced by

the Bab was to His ancestral home in Nur, in the

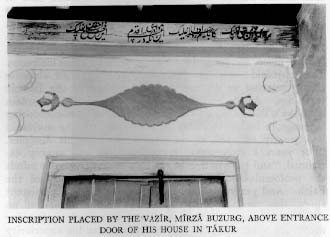

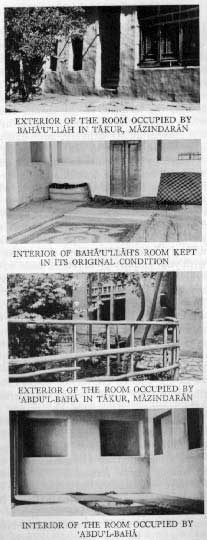

province of Mazindaran. He set out for the village

of Takur, the personal estate of His father, where He owned a

vast mansion, royally furnished and superbly situated. It

was my privilege to hear Baha'u'llah Himself, one day, recount

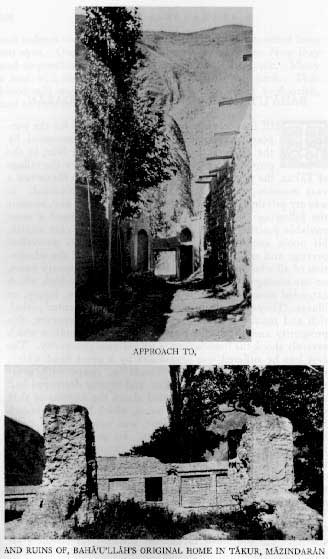

the following: "The late Vazir, My father, enjoyed a most

enviable position among his countrymen. His vast wealth,

his noble ancestry, his artistic attainments, his unrivalled

prestige and exalted rank made him the object of the admiration

of all who knew him. For a period of over twenty years,

no one among the wide circle of his family and kindred, which

extended over Nur and Tihran, suffered distress, injury, or

illness. They enjoyed, during a long and uninterrupted period,

rich and manifold blessings. Quite suddenly, however, this

prosperity and glory gave way to a series of calamities which

severely shook the foundations of his material prosperity. The

first loss he suffered was occasioned by a great flood which,

rising in the mountains of Mazindaran, swept with great

violence over the village of Takur, and utterly destroyed half

the mansion of the Vazir, situated above the fortress of that

village. The best part of that house, which had been known

for the solidity of its foundations, was utterly wiped away

by the fury of the roaring torrent. Its precious articles of

furniture were destroyed, and its elaborate ornamentation

irretrievably ruined. This was shortly followed by the loss

of various State positions which the Vazir occupied, and by

the repeated assaults directed against him by his envious

adversaries. Despite this sudden change of fortune, the

Vazir maintained his dignity and calm, and continued, within

the restricted limits of his means, his acts of benevolence and

charity. He continued to exercise towards his faithless associates

HE first journey Baha'u'llah

undertook for the purpose of promoting the Revelation announced by

the Bab was to His ancestral home in Nur, in the

province of Mazindaran. He set out for the village

of Takur, the personal estate of His father, where He owned a

vast mansion, royally furnished and superbly situated. It

was my privilege to hear Baha'u'llah Himself, one day, recount

the following: "The late Vazir, My father, enjoyed a most

enviable position among his countrymen. His vast wealth,

his noble ancestry, his artistic attainments, his unrivalled

prestige and exalted rank made him the object of the admiration

of all who knew him. For a period of over twenty years,

no one among the wide circle of his family and kindred, which

extended over Nur and Tihran, suffered distress, injury, or

illness. They enjoyed, during a long and uninterrupted period,

rich and manifold blessings. Quite suddenly, however, this

prosperity and glory gave way to a series of calamities which

severely shook the foundations of his material prosperity. The

first loss he suffered was occasioned by a great flood which,

rising in the mountains of Mazindaran, swept with great

violence over the village of Takur, and utterly destroyed half

the mansion of the Vazir, situated above the fortress of that

village. The best part of that house, which had been known

for the solidity of its foundations, was utterly wiped away

by the fury of the roaring torrent. Its precious articles of

furniture were destroyed, and its elaborate ornamentation

irretrievably ruined. This was shortly followed by the loss

of various State positions which the Vazir occupied, and by

the repeated assaults directed against him by his envious

adversaries. Despite this sudden change of fortune, the

Vazir maintained his dignity and calm, and continued, within

the restricted limits of his means, his acts of benevolence and

charity. He continued to exercise towards his faithless associates

Baha'u'llah had already, prior to the declaration of the

Bab, visited the district of Nur, at a time when the celebrated

mujtahid Mirza Muhammad Taqiy-i-Nuri was at the height

of his authority and influence. Such was the eminence of his

position, that they who sat at his feet regarded themselves

each as the authorised exponent of the Faith and Law of

Islam. The mujtahid was addressing a company of over

two hundred of such disciples, and was expatiating upon a

dark passage of the reported utterances of the imams, when

Baha'u'llah, followed by a number of His companions, passed

by that place, and paused for a while to listen to his discourse.

The mujtahid asked his disciples to elucidate an abstruse

theory relating to the metaphysical aspects of the Islamic

teachings. As they all confessed their inability to explain

it, Baha'u'llah was moved to give, in brief but convincing

language, a lucid exposition of that theory. The mujtahid

was greatly annoyed at the incompetence of his disciples.

"For years I have been instructing you," he angrily exclaimed,

"and have patiently striven to instil into your minds

the profoundest truths and the noblest principles of the

Faith. And yet you allow, after all these years of persistent

study, this youth, a wearer of the kulah,(1) who has had no

share in scholarly training, and who is entirely unfamiliar

with your academic learning, to demonstrate his superiority

over you!

Baha'u'llah had already, prior to the declaration of the

Bab, visited the district of Nur, at a time when the celebrated

mujtahid Mirza Muhammad Taqiy-i-Nuri was at the height

of his authority and influence. Such was the eminence of his

position, that they who sat at his feet regarded themselves

each as the authorised exponent of the Faith and Law of

Islam. The mujtahid was addressing a company of over

two hundred of such disciples, and was expatiating upon a

dark passage of the reported utterances of the imams, when

Baha'u'llah, followed by a number of His companions, passed

by that place, and paused for a while to listen to his discourse.

The mujtahid asked his disciples to elucidate an abstruse

theory relating to the metaphysical aspects of the Islamic

teachings. As they all confessed their inability to explain

it, Baha'u'llah was moved to give, in brief but convincing

language, a lucid exposition of that theory. The mujtahid

was greatly annoyed at the incompetence of his disciples.

"For years I have been instructing you," he angrily exclaimed,

"and have patiently striven to instil into your minds

the profoundest truths and the noblest principles of the

Faith. And yet you allow, after all these years of persistent

study, this youth, a wearer of the kulah,(1) who has had no

share in scholarly training, and who is entirely unfamiliar

with your academic learning, to demonstrate his superiority

over you!

Later on, when Baha'u'llah had departed, the mujtahid

related to his disciples two of his recent dreams, the circumstances

of which he believed were of the utmost significance.

"In my first dream," he said, "I was standing in the midst

of a vast concourse of people, all of whom seemed to be

pointing to a certain house in which they said the Sahibu'z-Zaman

dwelt. Frantic with joy, I hastened in my dream

to attain His presence. When I reached the house, I was,

to my great surprise, refused admittance. `The promised

Later on, when Baha'u'llah had departed, the mujtahid

related to his disciples two of his recent dreams, the circumstances

of which he believed were of the utmost significance.

"In my first dream," he said, "I was standing in the midst

of a vast concourse of people, all of whom seemed to be

pointing to a certain house in which they said the Sahibu'z-Zaman

dwelt. Frantic with joy, I hastened in my dream

to attain His presence. When I reached the house, I was,

to my great surprise, refused admittance. `The promised

"In my second dream," the mujtahid continued, "I found

myself in a place where I beheld around me a number of coffers,

each of which, it was stated, belonged to Baha'u'llah. As

I opened them, I found them to be filled with books. Every

word and letter recorded in these books was set with the most

"In my second dream," the mujtahid continued, "I found

myself in a place where I beheld around me a number of coffers,

each of which, it was stated, belonged to Baha'u'llah. As

I opened them, I found them to be filled with books. Every

word and letter recorded in these books was set with the most

When, in the year '60, Baha'u'llah arrived in Nur, He

discovered that the celebrated mujtahid who on His previous

visit had wielded such immense power had passed away.

The vast number of his devotees had shrunk into a mere

handful of dejected disciples who, under the leadership of

his successor, Mulla Muhammad, were striving to uphold

the traditions of their departed leader. The enthusiasm which

greeted Baha'u'llah's arrival sharply contrasted with the

When, in the year '60, Baha'u'llah arrived in Nur, He

discovered that the celebrated mujtahid who on His previous

visit had wielded such immense power had passed away.

The vast number of his devotees had shrunk into a mere

handful of dejected disciples who, under the leadership of

his successor, Mulla Muhammad, were striving to uphold

the traditions of their departed leader. The enthusiasm which

greeted Baha'u'llah's arrival sharply contrasted with the

None dared to contend with His views except His uncle

Aziz, who ventured to oppose Him, challenging His statements

and aspersing their truth. When those who heard

him sought to silence this opponent and to injure him, Baha'u'llah

intervened in his behalf, and advised them to leave

him in the hands of God. Alarmed, he sought the aid of the

mujtahid of Nur, Mulla Muhammad, and appealed to him

to lend him immediate assistance. "O vicegerent of the

Prophet of God!" he said. "Behold what has befallen the

Faith. A youth, a layman, attired in the garb of nobility,

has come to Nur, has invaded the strongholds of orthodoxy,

and disrupted the holy Faith of Islam. Arise, and resist his

onslaught. Whoever attains his presence falls immediately

under his spell, and is enthralled by the power of his utterance.

I know not whether he is a sorcerer, or whether he mixes

with his tea some mysterious substance that makes every

man who drinks the tea fall a victim to its charm." The

None dared to contend with His views except His uncle

Aziz, who ventured to oppose Him, challenging His statements

and aspersing their truth. When those who heard

him sought to silence this opponent and to injure him, Baha'u'llah

intervened in his behalf, and advised them to leave

him in the hands of God. Alarmed, he sought the aid of the

mujtahid of Nur, Mulla Muhammad, and appealed to him

to lend him immediate assistance. "O vicegerent of the

Prophet of God!" he said. "Behold what has befallen the

Faith. A youth, a layman, attired in the garb of nobility,

has come to Nur, has invaded the strongholds of orthodoxy,

and disrupted the holy Faith of Islam. Arise, and resist his

onslaught. Whoever attains his presence falls immediately

under his spell, and is enthralled by the power of his utterance.

I know not whether he is a sorcerer, or whether he mixes

with his tea some mysterious substance that makes every

man who drinks the tea fall a victim to its charm." The

Those who attained the presence of Baha'u'llah and heard

Him expound the Message proclaimed by the Bab were so

much impressed by the earnestness of His appeal that they

forthwith arose to disseminate that same Message among

the people of Nur and to extol the virtues of its distinguished

Promoter. The disciples of Mulla Muhammad meanwhile

endeavoured to persuade their teacher to proceed to Takur,

to visit Baha'u'llah in person, to ascertain from Him the nature

of this new Revelation, and to enlighten his followers regarding

its character and purpose. To their earnest entreaty the

mujtahid returned an evasive answer. His disciples, however,

refused to admit the validity of the objections he raised.

They urged that the first obligation imposed upon a man of

his position, whose function was to preserve the integrity of

shi'ah Islam, was to enquire into the nature of every movement

that tended to affect the interests of their Faith. Mulla

Muhammad eventually decided to delegate two of his eminent

lieutenants, Mulla Abbas and Mirza Abu'l-Qasim, both

sons-in-law and trusted disciples of the late mujtahid, Mirza

Muhammad-Taqi, to visit Baha'u'llah and to determine the

true character of the Message He had brought. He pledged

himself to endorse unreservedly whatever conclusions they

might arrive at, and to recognise their decision in such matters

as final.

Those who attained the presence of Baha'u'llah and heard

Him expound the Message proclaimed by the Bab were so

much impressed by the earnestness of His appeal that they

forthwith arose to disseminate that same Message among

the people of Nur and to extol the virtues of its distinguished

Promoter. The disciples of Mulla Muhammad meanwhile

endeavoured to persuade their teacher to proceed to Takur,

to visit Baha'u'llah in person, to ascertain from Him the nature

of this new Revelation, and to enlighten his followers regarding

its character and purpose. To their earnest entreaty the

mujtahid returned an evasive answer. His disciples, however,

refused to admit the validity of the objections he raised.

They urged that the first obligation imposed upon a man of

his position, whose function was to preserve the integrity of

shi'ah Islam, was to enquire into the nature of every movement

that tended to affect the interests of their Faith. Mulla

Muhammad eventually decided to delegate two of his eminent

lieutenants, Mulla Abbas and Mirza Abu'l-Qasim, both

sons-in-law and trusted disciples of the late mujtahid, Mirza

Muhammad-Taqi, to visit Baha'u'llah and to determine the

true character of the Message He had brought. He pledged

himself to endorse unreservedly whatever conclusions they

might arrive at, and to recognise their decision in such matters

as final.

On being informed, upon their arrival in Takur, that Baha'u'llah

had departed for His winter resort, the representatives

of Mulla Muhammad decided to leave for that place. When

they arrived, they found Baha'u'llah engaged in revealing a

commentary on the opening Surih of the Qur'an, entitled

"The Seven Verses of Repetition." As they sat and listened

to His discourse, the loftiness of the theme, the persuasive

eloquence which characterised its presentation, as well as the

extraordinary manner of its delivery, profoundly impressed

them. Mulla Abbas, unable to contain himself, arose from

his seat and, urged by an impulse he could not resist, walked

back and stood still beside the door in an attitude of reverent

submissiveness. The charm of the discourse to which he was

listening had fascinated him. "You behold my condition,"

he told his companion as he stood trembling with emotion

and with eyes full of tears. "I am powerless to question

Baha'u'llah. The questions I had planned to ask Him have

vanished suddenly from my memory. You are free either

to proceed with your enquiry or to return alone to our teacher

and inform him of the state in which I find myself. Tell

him from me that Abbas can never again return to him.

He can no longer forsake this threshold." Mirza Abu'l-Qasim

was likewise moved to follow the example of his companion.

"I have ceased to recognise my teacher," was his reply. "This

very moment, I have vowed to God to dedicate the remaining

days of my life to the service of Baha'u'llah, my true and

only Master."

On being informed, upon their arrival in Takur, that Baha'u'llah

had departed for His winter resort, the representatives

of Mulla Muhammad decided to leave for that place. When

they arrived, they found Baha'u'llah engaged in revealing a

commentary on the opening Surih of the Qur'an, entitled

"The Seven Verses of Repetition." As they sat and listened

to His discourse, the loftiness of the theme, the persuasive

eloquence which characterised its presentation, as well as the

extraordinary manner of its delivery, profoundly impressed

them. Mulla Abbas, unable to contain himself, arose from

his seat and, urged by an impulse he could not resist, walked

back and stood still beside the door in an attitude of reverent

submissiveness. The charm of the discourse to which he was

listening had fascinated him. "You behold my condition,"

he told his companion as he stood trembling with emotion

and with eyes full of tears. "I am powerless to question

Baha'u'llah. The questions I had planned to ask Him have

vanished suddenly from my memory. You are free either

to proceed with your enquiry or to return alone to our teacher

and inform him of the state in which I find myself. Tell

him from me that Abbas can never again return to him.

He can no longer forsake this threshold." Mirza Abu'l-Qasim

was likewise moved to follow the example of his companion.

"I have ceased to recognise my teacher," was his reply. "This

very moment, I have vowed to God to dedicate the remaining

days of my life to the service of Baha'u'llah, my true and

only Master."

The news of the sudden conversion of the chosen envoys

of the mujtahid of Nur spread with bewildering rapidity

throughout the district. It roused the people from their

lethargy. Ecclesiastical dignitaries, State officials, traders,

and peasants all flocked to the residence of Baha'u'llah. A

considerable number among them willingly espoused His

Cause. In their admiration for Him, a number of the most

distinguished among them remarked: "We see how the

people of Nur have risen and rallied round you. We witness

on every side evidences of their exultation. If Mulla Muhammad

were also to join them, the triumph of this Faith

would be completely assured." "I am come to Nur," Baha'u'llah

replied, "solely for the purpose of proclaiming the

The news of the sudden conversion of the chosen envoys

of the mujtahid of Nur spread with bewildering rapidity

throughout the district. It roused the people from their

lethargy. Ecclesiastical dignitaries, State officials, traders,

and peasants all flocked to the residence of Baha'u'llah. A

considerable number among them willingly espoused His

Cause. In their admiration for Him, a number of the most

distinguished among them remarked: "We see how the

people of Nur have risen and rallied round you. We witness

on every side evidences of their exultation. If Mulla Muhammad

were also to join them, the triumph of this Faith

would be completely assured." "I am come to Nur," Baha'u'llah

replied, "solely for the purpose of proclaiming the

Desirous of giving effect to His words, Baha'u'llah, accompanied

by a number of His companions, proceeded immediately

to that village. Mulla Muhammad most ceremoniously

received Him. "I have not come to this place,"

Baha'u'llah observed, "to pay you an official or formal visit.

My purpose is to enlighten you regarding a new and wondrous

Message, divinely inspired and fulfilling the promise given to

Islam. Whosoever has inclined his ear to this Message has

felt its irresistible power, and has been transformed by the

potency of its grace. Tell Me whatsoever perplexes your

mind, or hinders you from recognising the Truth." Mulla

Muhammad disparagingly remarked: "I undertake no action

unless I first consult the Qur'an. I have invariably, on such

occasions, followed the practice of invoking the aid of God

and His blessings; of opening at random His sacred Book,

and of consulting the first verse of the particular page upon

which my eyes chance to fall. From the nature of that

verse I can judge the wisdom and the advisability of my

contemplated course of action." Finding that Baha'u'llah

was not inclined to refuse him his request, the mujtahid called

for a copy of the Qur'an, opened and closed it again, refusing

to reveal the nature of the verse to those who were present.

All he said was this: "I have consulted the Book of God, and

deem it inadvisable to proceed further with this matter."

A few agreed with him; the rest, for the most part, did not

fail to recognise the fear which those words implied. Baha'u'llah,

disinclined to cause him further embarrassment, arose

and, asking to be excused, bade him a cordial farewell.

Desirous of giving effect to His words, Baha'u'llah, accompanied

by a number of His companions, proceeded immediately

to that village. Mulla Muhammad most ceremoniously

received Him. "I have not come to this place,"

Baha'u'llah observed, "to pay you an official or formal visit.

My purpose is to enlighten you regarding a new and wondrous

Message, divinely inspired and fulfilling the promise given to

Islam. Whosoever has inclined his ear to this Message has

felt its irresistible power, and has been transformed by the

potency of its grace. Tell Me whatsoever perplexes your

mind, or hinders you from recognising the Truth." Mulla

Muhammad disparagingly remarked: "I undertake no action

unless I first consult the Qur'an. I have invariably, on such

occasions, followed the practice of invoking the aid of God

and His blessings; of opening at random His sacred Book,

and of consulting the first verse of the particular page upon

which my eyes chance to fall. From the nature of that

verse I can judge the wisdom and the advisability of my

contemplated course of action." Finding that Baha'u'llah

was not inclined to refuse him his request, the mujtahid called

for a copy of the Qur'an, opened and closed it again, refusing

to reveal the nature of the verse to those who were present.

All he said was this: "I have consulted the Book of God, and

deem it inadvisable to proceed further with this matter."

A few agreed with him; the rest, for the most part, did not

fail to recognise the fear which those words implied. Baha'u'llah,

disinclined to cause him further embarrassment, arose

and, asking to be excused, bade him a cordial farewell.

One day, in the course of one of His riding excursions into

the country, Baha'u'llah, accompanied by His companions,

saw, seated by Me roadside, a lonely youth. His hair was

dishevelled, and he wore the dress of a dervish. By the side

of a brook he had kindled a fire, and was cooking his food

One day, in the course of one of His riding excursions into

the country, Baha'u'llah, accompanied by His companions,

saw, seated by Me roadside, a lonely youth. His hair was

dishevelled, and he wore the dress of a dervish. By the side

of a brook he had kindled a fire, and was cooking his food

Baha'u'llah's visit to Nur had produced the most far-reaching

results, and had lent a remarkable impetus to the

spread of the new-born Revelation. By His magnetic eloquence,

by the purity of His life, by the dignity of His bearing,

by the unanswerable logic of His argument, and by the many

evidences of His loving-kindness, Baha'u'llah had won the

hearts of the people of Nur, had stirred their souls, and had

enrolled them under the standard of the Faith. Such was

the effect of words and deeds, as He went about preaching

the Cause and revealing its glory to His countrymen in Nur,

that the very stones and trees of that district seemed to have

Baha'u'llah's visit to Nur had produced the most far-reaching

results, and had lent a remarkable impetus to the

spread of the new-born Revelation. By His magnetic eloquence,

by the purity of His life, by the dignity of His bearing,

by the unanswerable logic of His argument, and by the many

evidences of His loving-kindness, Baha'u'llah had won the

hearts of the people of Nur, had stirred their souls, and had

enrolled them under the standard of the Faith. Such was

the effect of words and deeds, as He went about preaching

the Cause and revealing its glory to His countrymen in Nur,

that the very stones and trees of that district seemed to have

When Baha'u'llah was still a child, the Vazir, His father,

dreamed a dream. Baha'u'llah appeared to him swimming

in a vast, limitless ocean. His body shone upon the waters

with a radiance that illumined the sea. Around His head,

which could distinctly be seen above the waters, there radiated,

in all directions, His long, jet-black locks, floating in

great profusion above the waves. As he dreamed, a multitude

of fishes gathered round Him, each holding fast to the

extremity of one hair. Fascinated by the effulgence of His

face, they followed Him in whatever direction He swam.

Great as was their number, and however firmly they clung

to His locks, not one single hair seemed to have been detached

from His head, nor did the least injury affect His

person. Free and unrestrained, He moved above the waters

and they all followed Him.

When Baha'u'llah was still a child, the Vazir, His father,

dreamed a dream. Baha'u'llah appeared to him swimming

in a vast, limitless ocean. His body shone upon the waters

with a radiance that illumined the sea. Around His head,

which could distinctly be seen above the waters, there radiated,

in all directions, His long, jet-black locks, floating in

great profusion above the waves. As he dreamed, a multitude

of fishes gathered round Him, each holding fast to the

extremity of one hair. Fascinated by the effulgence of His

face, they followed Him in whatever direction He swam.

Great as was their number, and however firmly they clung

to His locks, not one single hair seemed to have been detached

from His head, nor did the least injury affect His

person. Free and unrestrained, He moved above the waters

and they all followed Him.

The Vazir, greatly impressed by this dream, summoned

a soothsayer, who had achieved fame in that region, and

asked him to interpret it for him. This man, as if inspired

by a premonition of the future glory of Baha'u'llah, declared:

"The limitless ocean that you have seen in your dream, O

The Vazir, greatly impressed by this dream, summoned

a soothsayer, who had achieved fame in that region, and

asked him to interpret it for him. This man, as if inspired

by a premonition of the future glory of Baha'u'llah, declared:

"The limitless ocean that you have seen in your dream, O

That soothsayer was subsequently taken to see Baha'u'llah.

He looked intently upon His face, and examined carefully

His features. He was charmed by His appearance, and

extolled every trait of His countenance. Every expression

in that face revealed to his eyes a sign of His concealed glory.

So great was his admiration, and so profuse his praise of

Baha'u'llah, that the Vazir, from that day, became even

more passionately devoted to his son. The words spoken by

that soothsayer served to fortify his hopes and confidence

in Him. Like Jacob, he desired only to ensure the welfare

of his beloved Joseph, and to surround Him with his loving

protection.

That soothsayer was subsequently taken to see Baha'u'llah.

He looked intently upon His face, and examined carefully

His features. He was charmed by His appearance, and

extolled every trait of His countenance. Every expression

in that face revealed to his eyes a sign of His concealed glory.

So great was his admiration, and so profuse his praise of

Baha'u'llah, that the Vazir, from that day, became even

more passionately devoted to his son. The words spoken by

that soothsayer served to fortify his hopes and confidence

in Him. Like Jacob, he desired only to ensure the welfare

of his beloved Joseph, and to surround Him with his loving

protection.

Haji Mirza Aqasi, the Grand Vazir of Muhammad Shah,

though completely alienated from Baha'u'llah's father, showed

his son every mark of consideration and favour. So great

was the esteem which the Haji professed for Him, that Mirza

Aqa Khan-i-Nuri, the I'timadu'd-Dawlih, who afterwards

succeeded Haji Mirza Aqasi, felt envious. He resented the

superiority which Baha'u'llah, as a mere youth, was accorded

over him. The seeds of jealousy were, from that time, implanted

in his breast. Though still a youth, and while his

father is yet alive, he thought, he is given precedence in the

presence of the Grand Vazir. What will, I wonder, happen

to me when this young man shall have succeeded his father?

Haji Mirza Aqasi, the Grand Vazir of Muhammad Shah,

though completely alienated from Baha'u'llah's father, showed

his son every mark of consideration and favour. So great

was the esteem which the Haji professed for Him, that Mirza

Aqa Khan-i-Nuri, the I'timadu'd-Dawlih, who afterwards

succeeded Haji Mirza Aqasi, felt envious. He resented the

superiority which Baha'u'llah, as a mere youth, was accorded

over him. The seeds of jealousy were, from that time, implanted

in his breast. Though still a youth, and while his

father is yet alive, he thought, he is given precedence in the

presence of the Grand Vazir. What will, I wonder, happen

to me when this young man shall have succeeded his father?

After the death of the Vazir, Haji Mirza Aqasi continued

to show the utmost consideration to Baha'u'llah. He would

visit Him in His home, and would address Him as though

He were his own son. The sincerity of his devotion, however,

was very soon put to the test. One day, as he was passing

through the village of Quch-Hisar, which belonged to Baha'u'llah,

After the death of the Vazir, Haji Mirza Aqasi continued

to show the utmost consideration to Baha'u'llah. He would

visit Him in His home, and would address Him as though

He were his own son. The sincerity of his devotion, however,

was very soon put to the test. One day, as he was passing

through the village of Quch-Hisar, which belonged to Baha'u'llah,

On a number of other occasions, Baha'u'llah's ascendancy

over His opponents was likewise vindicated and recognised.

These personal triumphs achieved by Him served to enhance

His position, and spread abroad His fame. All classes of

men marvelled at His miraculous success in emerging unscathed

from the most perilous encounters. Nothing short

of Divine protection, they thought, could have ensured His

safety on such occasions. Not once did Baha'u'llah, beset

though He was by the gravest perils, submit to the arrogance,

the greed, and the treachery of those around Him. In His

constant association, during those days, with the highest

dignitaries of the realm, whether ecclesiastical or State officials,

He was never content simply to accede to the views

they expressed or the claims they advanced. He would, at

their gatherings, fearlessly champion the cause of truth,

would assert the rights of the downtrodden, defending the

weak and protecting the innocent.

On a number of other occasions, Baha'u'llah's ascendancy

over His opponents was likewise vindicated and recognised.

These personal triumphs achieved by Him served to enhance

His position, and spread abroad His fame. All classes of

men marvelled at His miraculous success in emerging unscathed

from the most perilous encounters. Nothing short

of Divine protection, they thought, could have ensured His

safety on such occasions. Not once did Baha'u'llah, beset

though He was by the gravest perils, submit to the arrogance,

the greed, and the treachery of those around Him. In His

constant association, during those days, with the highest

dignitaries of the realm, whether ecclesiastical or State officials,

He was never content simply to accede to the views

they expressed or the claims they advanced. He would, at

their gatherings, fearlessly champion the cause of truth,

would assert the rights of the downtrodden, defending the

weak and protecting the innocent.

|