HE summer of the year 1262 A.H.(1) was drawing to

a close when the Bab bade His last farewell to

His native city of Shiraz, and proceeded to Isfahan.

Siyyid Kazim-i-Zanjani accompanied Him on that

journey. As He approached the outskirts of the city, He

wrote a letter to the governor of the province, Manuchihr

Khan, the Mu'tamidu'd-Dawlih,(2) in which He requested

him to signify his wish as to the place where He could dwell.

The letter, which He entrusted to Siyyid Kazim, was expressive

of such courtesy and revealed such exquisite penmanship

that the Mu'tamid was moved to instruct the

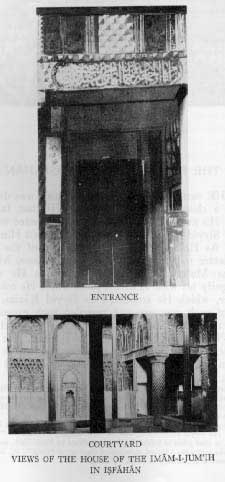

Sultanu'l-'Ulama, the Imam-Jum'ih of Isfahan,'(3) the foremost

ecclesiastical authority of that province, to receive the Bab

in his own home and to accord Him a kindly and generous

HE summer of the year 1262 A.H.(1) was drawing to

a close when the Bab bade His last farewell to

His native city of Shiraz, and proceeded to Isfahan.

Siyyid Kazim-i-Zanjani accompanied Him on that

journey. As He approached the outskirts of the city, He

wrote a letter to the governor of the province, Manuchihr

Khan, the Mu'tamidu'd-Dawlih,(2) in which He requested

him to signify his wish as to the place where He could dwell.

The letter, which He entrusted to Siyyid Kazim, was expressive

of such courtesy and revealed such exquisite penmanship

that the Mu'tamid was moved to instruct the

Sultanu'l-'Ulama, the Imam-Jum'ih of Isfahan,'(3) the foremost

ecclesiastical authority of that province, to receive the Bab

in his own home and to accord Him a kindly and generous

Such were the honours accorded to the Bab in those days

that when, on a certain Friday, He was returning from the

public bath to the house, a multitude of people were seen

eagerly clamouring for the water which He had used for His

ablutions. His fervent admirers firmly believed in its unfailng

virtue and power to heal their sicknesses and ailments.

The Imam-Jum'ih himself had, from the very first night,

become so enamoured with Him who was the object of such

devotion, that, assuming the functions of an attendant,

he undertook to minister to the needs and wants of his beloved

Guest. Seizing the ewer from the hand of the chief

steward and utterly ignoring the customary dignity of his

rank, he proceeded to pour out the water over the hands of

the Bab.

Such were the honours accorded to the Bab in those days

that when, on a certain Friday, He was returning from the

public bath to the house, a multitude of people were seen

eagerly clamouring for the water which He had used for His

ablutions. His fervent admirers firmly believed in its unfailng

virtue and power to heal their sicknesses and ailments.

The Imam-Jum'ih himself had, from the very first night,

become so enamoured with Him who was the object of such

devotion, that, assuming the functions of an attendant,

he undertook to minister to the needs and wants of his beloved

Guest. Seizing the ewer from the hand of the chief

steward and utterly ignoring the customary dignity of his

rank, he proceeded to pour out the water over the hands of

the Bab.

One night, after supper, the Imam-Jum'ih, whose curiosity

had been excited by the extraordinary traits of character

which his youthful Guest had revealed, ventured to request

Him to reveal a commentary on the Surih of Va'l-'Asr.(2)

His request was readily granted. Calling for pen and paper,

the Bab, with astonishing rapidity and without the least

premeditation, began to reveal, in the presence of His host,

a most illuminating interpretation of the aforementioned

Surih. It was nearing midnight when the Bab found Himself

engaged in the exposition of the manifold implications involved

in the first letter of that Surih. That letter, the letter

` vav' upon which Shaykh Ahmad-i-Ahsa'i had already laid such

emphasis in his writings, symbolised for the Bab the advent

of a new cycle of Divine Revelation, and has since been

alluded to by Baha'u'llah in the "Kitab-i-Aqdas" in such

passages as "the mastery of the Great Reversal" and "the

Sign of the Sovereign." The Bab soon after began to chant,

in the presence of His host and his companions, the homily

with which He had prefaced His commentary on the Surih.

Those words of power confounded His hearers with wonder.

One night, after supper, the Imam-Jum'ih, whose curiosity

had been excited by the extraordinary traits of character

which his youthful Guest had revealed, ventured to request

Him to reveal a commentary on the Surih of Va'l-'Asr.(2)

His request was readily granted. Calling for pen and paper,

the Bab, with astonishing rapidity and without the least

premeditation, began to reveal, in the presence of His host,

a most illuminating interpretation of the aforementioned

Surih. It was nearing midnight when the Bab found Himself

engaged in the exposition of the manifold implications involved

in the first letter of that Surih. That letter, the letter

` vav' upon which Shaykh Ahmad-i-Ahsa'i had already laid such

emphasis in his writings, symbolised for the Bab the advent

of a new cycle of Divine Revelation, and has since been

alluded to by Baha'u'llah in the "Kitab-i-Aqdas" in such

passages as "the mastery of the Great Reversal" and "the

Sign of the Sovereign." The Bab soon after began to chant,

in the presence of His host and his companions, the homily

with which He had prefaced His commentary on the Surih.

Those words of power confounded His hearers with wonder.

As the Bab's fame was being gradually diffused over the

entire city of Isfahan, an unceasing stream of visitors flowed

from every quarter to the house of the Imam-Jum'ih: a few

to satisfy their curiosity, others to obtain a deeper understanding

of the fundamental verities of His Faith, and still

others to seek the remedy for their ills and sufferings. The

Mu'tamid himself came one day to visit the Bab and, while

seated in the midst of an assemblage of the most brilliant

and accomplished divines of Isfahan, requested Him to expound

the nature and demonstrate the validity of the Nubuvvat-i-Khassih.(1) He had previously, in that same gathering, called upon those who were present to adduce such

proofs and evidences in support of this fundamental article

of their Faith as would constitute an unanswerable testimony

for those who were inclined to repudiate its truth. No one,

however, seemed capable of responding to his invitation.

"Which do you prefer," asked the Bab, "a verbal or a written

answer to your question?" "A written reply," he answered,

"not only would please those who are present at this meeting,

but would edify and instruct both the present and future

generations."

As the Bab's fame was being gradually diffused over the

entire city of Isfahan, an unceasing stream of visitors flowed

from every quarter to the house of the Imam-Jum'ih: a few

to satisfy their curiosity, others to obtain a deeper understanding

of the fundamental verities of His Faith, and still

others to seek the remedy for their ills and sufferings. The

Mu'tamid himself came one day to visit the Bab and, while

seated in the midst of an assemblage of the most brilliant

and accomplished divines of Isfahan, requested Him to expound

the nature and demonstrate the validity of the Nubuvvat-i-Khassih.(1) He had previously, in that same gathering, called upon those who were present to adduce such

proofs and evidences in support of this fundamental article

of their Faith as would constitute an unanswerable testimony

for those who were inclined to repudiate its truth. No one,

however, seemed capable of responding to his invitation.

"Which do you prefer," asked the Bab, "a verbal or a written

answer to your question?" "A written reply," he answered,

"not only would please those who are present at this meeting,

but would edify and instruct both the present and future

generations."

The Bab instantly took up His pen and began to write.

In less than two hours, He had filled about fifty pages with

a most refreshing and circumstantial enquiry into the origin,

the character, and the pervasive influence of Islam. The

originality of His dissertation, the vigour and vividness of

The Bab instantly took up His pen and began to write.

In less than two hours, He had filled about fifty pages with

a most refreshing and circumstantial enquiry into the origin,

the character, and the pervasive influence of Islam. The

originality of His dissertation, the vigour and vividness of

The growing popularity of the Bab aroused the resentment

of the ecclesiastical authorities of Isfahan, who viewed

with concern and envy the ascendancy which an unlearned

Youth was slowly acquiring over the thoughts and consciences

of their followers. They firmly believed that unless they

rose to stem the tide of popular enthusiasm, the very foundations

of their existence would be undermined. A few of the

more sagacious among them thought it wise to abstain from

acts of direct hostility to either the person or the teachings

of the Bab, as such action, they felt, would serve only to

enhance His prestige and consolidate His position. The

mischief-makers, however, were busily engaged in disseminating

the wildest reports concerning the character and

claims of the Bab. These reports soon reached Tihran

and were brought to the attention of Haji Mirza Aqasi, the

Grand Vazir of Muhammad Shah. This haughty and overbearing

minister viewed with apprehension the possibility

that his sovereign might one day feel inclined to befriend

the Bab, an inclination which he felt sure would precipitate

his own downfall. The Haji was, moreover, apprehensive

lest the Mu'tamid, who enjoyed the confidence of the Shah,

should succeed in arranging an interview between the sovereign

and the Bab. He was well aware that should such an

interview take place, the impressionable and tender-hearted

Muhammad Shah would be completely won over by the

attractiveness and novelty of that creed. Spurred on by

The growing popularity of the Bab aroused the resentment

of the ecclesiastical authorities of Isfahan, who viewed

with concern and envy the ascendancy which an unlearned

Youth was slowly acquiring over the thoughts and consciences

of their followers. They firmly believed that unless they

rose to stem the tide of popular enthusiasm, the very foundations

of their existence would be undermined. A few of the

more sagacious among them thought it wise to abstain from

acts of direct hostility to either the person or the teachings

of the Bab, as such action, they felt, would serve only to

enhance His prestige and consolidate His position. The

mischief-makers, however, were busily engaged in disseminating

the wildest reports concerning the character and

claims of the Bab. These reports soon reached Tihran

and were brought to the attention of Haji Mirza Aqasi, the

Grand Vazir of Muhammad Shah. This haughty and overbearing

minister viewed with apprehension the possibility

that his sovereign might one day feel inclined to befriend

the Bab, an inclination which he felt sure would precipitate

his own downfall. The Haji was, moreover, apprehensive

lest the Mu'tamid, who enjoyed the confidence of the Shah,

should succeed in arranging an interview between the sovereign

and the Bab. He was well aware that should such an

interview take place, the impressionable and tender-hearted

Muhammad Shah would be completely won over by the

attractiveness and novelty of that creed. Spurred on by

As soon as the Mu'tamid was informed of these developments,

he sent a message to the Imam-Jum'ih in which he

reminded him of the visit he as governor had paid to the

Bab, and extended to him as well as to his Guest an invitation

to his home. The Mu'tamid invited Haji Siyyid Asadu'llah,

son of the late Haji Siyyid Muhammad Baqir-i-Rashti,

Haji Muhammad-Ja'far-i-Abadiyi, Muhammad-Mihdi, Mirza

Hasan-i-Nuri, and a few others to be present at that meeting.

Haji Siyyid Asadu'llah refused the invitation and endeavoured

to dissuade those who had been invited, from participating

in that gathering. "I have sought to excuse myself," he

informed them, "and I would most certainly urge you to do

the same. I regard it as most unwise of you to meet the

Siyyid-i-Bab face to face. He will, no doubt, reassert his

claim and will, in support of his argument, adduce whatever

proof you may desire him to give, and, without the least

hesitation, will reveal as a testimony to the truth he bears,

verses of such a number as would equal half the Qur'an. In

the end he will challenge you in these words: `Produce likewise,

As soon as the Mu'tamid was informed of these developments,

he sent a message to the Imam-Jum'ih in which he

reminded him of the visit he as governor had paid to the

Bab, and extended to him as well as to his Guest an invitation

to his home. The Mu'tamid invited Haji Siyyid Asadu'llah,

son of the late Haji Siyyid Muhammad Baqir-i-Rashti,

Haji Muhammad-Ja'far-i-Abadiyi, Muhammad-Mihdi, Mirza

Hasan-i-Nuri, and a few others to be present at that meeting.

Haji Siyyid Asadu'llah refused the invitation and endeavoured

to dissuade those who had been invited, from participating

in that gathering. "I have sought to excuse myself," he

informed them, "and I would most certainly urge you to do

the same. I regard it as most unwise of you to meet the

Siyyid-i-Bab face to face. He will, no doubt, reassert his

claim and will, in support of his argument, adduce whatever

proof you may desire him to give, and, without the least

hesitation, will reveal as a testimony to the truth he bears,

verses of such a number as would equal half the Qur'an. In

the end he will challenge you in these words: `Produce likewise,

Haji Muhammad-Ja'far heeded this counsel and refused

to accept the invitation of the governor. Muhammad Mihdi,

Mirza Hasan-i-Nuri, and a few others who disdained such

advice, presented themselves at the appointed hour at the

home of the Mu'tamid. At the invitation of the host, Mirza

Hasan, a noted Platonist, requested the Bab to elucidate

certain abstruse philosophical doctrines connected with the

Arshiyyih of Mulla Sadra,(1) the meaning of which only a

few had been able to unravel.(2) In simple and unconventional

language, the Bab replied to each of his questions.

Mirza Hasan, though unable to apprehend the meaning of

the answers which he had received, realised how inferior

was the learning of the so-called exponents of the Platonic

and the Aristotelian schools of thought of his day to the

knowledge displayed by that Youth. Muhammad Mihdi

ventured in his turn to question the Bab regarding certain

aspects of the Islamic law. Dissatisfied with the explanation

he received, he began to contend idly with the Bab. He was

soon silenced by the Mu'tamid, who, cutting short his conversation,

turned to an attendant and, bidding him light the

lantern, gave the order that Muhammad Mihdi be immediately

conducted to his home. The Mu'tamid subsequently

Haji Muhammad-Ja'far heeded this counsel and refused

to accept the invitation of the governor. Muhammad Mihdi,

Mirza Hasan-i-Nuri, and a few others who disdained such

advice, presented themselves at the appointed hour at the

home of the Mu'tamid. At the invitation of the host, Mirza

Hasan, a noted Platonist, requested the Bab to elucidate

certain abstruse philosophical doctrines connected with the

Arshiyyih of Mulla Sadra,(1) the meaning of which only a

few had been able to unravel.(2) In simple and unconventional

language, the Bab replied to each of his questions.

Mirza Hasan, though unable to apprehend the meaning of

the answers which he had received, realised how inferior

was the learning of the so-called exponents of the Platonic

and the Aristotelian schools of thought of his day to the

knowledge displayed by that Youth. Muhammad Mihdi

ventured in his turn to question the Bab regarding certain

aspects of the Islamic law. Dissatisfied with the explanation

he received, he began to contend idly with the Bab. He was

soon silenced by the Mu'tamid, who, cutting short his conversation,

turned to an attendant and, bidding him light the

lantern, gave the order that Muhammad Mihdi be immediately

conducted to his home. The Mu'tamid subsequently

The Bab had tarried forty days at the residence of the

Imam-Jum'ih. While He was still there, a certain Mulla

Muhammad-Taqiy-i-Harati, who was privileged to meet the

Bab every day, undertook, with His consent, to translate

one of His works, entitled Risaliy-i-Furu'-i-'Adliyyih, from

the original Arabic into Persian. The service he thereby

rendered to the Persian believers was marred, however, by

his subsequent behaviour. Fear suddenly seized him, and

he was induced eventually to sever his connection with his

fellow-believers.

The Bab had tarried forty days at the residence of the

Imam-Jum'ih. While He was still there, a certain Mulla

Muhammad-Taqiy-i-Harati, who was privileged to meet the

Bab every day, undertook, with His consent, to translate

one of His works, entitled Risaliy-i-Furu'-i-'Adliyyih, from

the original Arabic into Persian. The service he thereby

rendered to the Persian believers was marred, however, by

his subsequent behaviour. Fear suddenly seized him, and

he was induced eventually to sever his connection with his

fellow-believers.

Ere the Bab had transferred His residence to the house

of the Mu'tamid, Mirza Ibrahim, father of the Sultanu'sh-Shuhada'

and elder brother of Mirza Muhammad-'Aliy-i-Nahri,

to whom we have already referred, invited the Bab

to his home one night. Mirza Ibrahim was a friend of the

Imam-Jum'ih, was intimately associated with him, and controlled

the management of all his affairs. The banquet which

was spread for the Bab that night was one of unsurpassed

magnificence. It was commonly observed that neither the

officials nor the notables of the city had offered a feast of

such magnitude and splendour. The Sultanu'sh-Shuhada'

and his brother, the Mahbubu'sh-Shuhada', who were lads

of nine and eleven, respectively, served at that banquet and

received special attention from the Bab. That night, during

dinner, Mirza Ibrahim turned to his Guest and said: "My

brother, Mirza Muhammad-'Ali, has no child. I beg You

to intercede in his behalf and to grant his heart's desire."

The Bab took a portion of the food with which He had been

served, placed it with His own hands on a platter, and handed

it to His host, asking him to take it to Mirza Muhammad-'Ali

and his wife. "Let them both partake of this," He said;

"their wish will be fulfilled." By virtue of that portion which

the Bab had chosen to bestow upon her, the wife of Mirza

Ere the Bab had transferred His residence to the house

of the Mu'tamid, Mirza Ibrahim, father of the Sultanu'sh-Shuhada'

and elder brother of Mirza Muhammad-'Aliy-i-Nahri,

to whom we have already referred, invited the Bab

to his home one night. Mirza Ibrahim was a friend of the

Imam-Jum'ih, was intimately associated with him, and controlled

the management of all his affairs. The banquet which

was spread for the Bab that night was one of unsurpassed

magnificence. It was commonly observed that neither the

officials nor the notables of the city had offered a feast of

such magnitude and splendour. The Sultanu'sh-Shuhada'

and his brother, the Mahbubu'sh-Shuhada', who were lads

of nine and eleven, respectively, served at that banquet and

received special attention from the Bab. That night, during

dinner, Mirza Ibrahim turned to his Guest and said: "My

brother, Mirza Muhammad-'Ali, has no child. I beg You

to intercede in his behalf and to grant his heart's desire."

The Bab took a portion of the food with which He had been

served, placed it with His own hands on a platter, and handed

it to His host, asking him to take it to Mirza Muhammad-'Ali

and his wife. "Let them both partake of this," He said;

"their wish will be fulfilled." By virtue of that portion which

the Bab had chosen to bestow upon her, the wife of Mirza

The high honours accorded to the Bab served further to

inflame the hostility of the ulamas of Isfahan. With feelings

of dismay, they beheld on every side evidences of His all-pervasive

influence invading the stronghold of orthodoxy and

subverting their foundations. They summoned a gathering,

at which they issued a written document, signed and sealed

by all the ecclesiastical leaders of the city, condemning the

Bab to death.(2) They all concurred in this condemnation

with the exception of Haji Siyyid Asadu'llah and Haji

Muhammad-Ja'far-i-Abadiyi, both of whom refused to associate

themselves with the contents of so glaringly abusive a document.

The Imam-Jum'ih, though declining to endorse the

death-warrant of the Bab, was induced, by reason of his

extreme cowardice and ambition, to add to that document,

in his own handwriting, the following testimony: "I testify

that in the course of my association with this youth I have

been unable to discover any act that would in any way

betray his repudiation of the doctrines of Islam. On the

contrary, I have known him as a pious and loyal observer

of its precepts. The extravagance of his claims, however,

and his disdainful contempt for the things of the world,

incline me to believe that he is devoid of reason and judgment."

The high honours accorded to the Bab served further to

inflame the hostility of the ulamas of Isfahan. With feelings

of dismay, they beheld on every side evidences of His all-pervasive

influence invading the stronghold of orthodoxy and

subverting their foundations. They summoned a gathering,

at which they issued a written document, signed and sealed

by all the ecclesiastical leaders of the city, condemning the

Bab to death.(2) They all concurred in this condemnation

with the exception of Haji Siyyid Asadu'llah and Haji

Muhammad-Ja'far-i-Abadiyi, both of whom refused to associate

themselves with the contents of so glaringly abusive a document.

The Imam-Jum'ih, though declining to endorse the

death-warrant of the Bab, was induced, by reason of his

extreme cowardice and ambition, to add to that document,

in his own handwriting, the following testimony: "I testify

that in the course of my association with this youth I have

been unable to discover any act that would in any way

betray his repudiation of the doctrines of Islam. On the

contrary, I have known him as a pious and loyal observer

of its precepts. The extravagance of his claims, however,

and his disdainful contempt for the things of the world,

incline me to believe that he is devoid of reason and judgment."

No sooner had the Mu'tamid been informed of the condemnation

pronounced by the ulamas of Isfahan than he

determined, by a plan which he himself conceived, to nullify

the effects of that cruel verdict. He issued immediate instructions

that towards the hour of sunset the Bab, escorted

by five hundred horsemen of the governor's own mounted

body-guard, should leave the gate of the city and proceed

in the direction of Tihran. Imperative orders had been

given that at the completion of each farsang(3) one hundred

of this mounted escort should return directly to Isfahan.

No sooner had the Mu'tamid been informed of the condemnation

pronounced by the ulamas of Isfahan than he

determined, by a plan which he himself conceived, to nullify

the effects of that cruel verdict. He issued immediate instructions

that towards the hour of sunset the Bab, escorted

by five hundred horsemen of the governor's own mounted

body-guard, should leave the gate of the city and proceed

in the direction of Tihran. Imperative orders had been

given that at the completion of each farsang(3) one hundred

of this mounted escort should return directly to Isfahan.

remaining hundred should likewise be

ordered by him to return to the city.

Of the twenty remaining horsemen, the

Mu'tamid directed that ten should be

despatched to Ardistan for the purpose

of collecting the taxes levied by the

government, and that the rest, all of

whom should be of his tried and most

reliable men, should, by an unfrequented

route, bring the Bab back in

disguise to Isfahan.(1) They were, moreover,

instructed so to regulate their

march that before dawn of the ensuing

day the Bab should have arrived at

Isfahan and should have been delivered

into his custody. This plan was

immediately taken in hand and duly

executed. At an unsuspected hour the

Bab re-entered the city, was directly

conducted to the private residence of

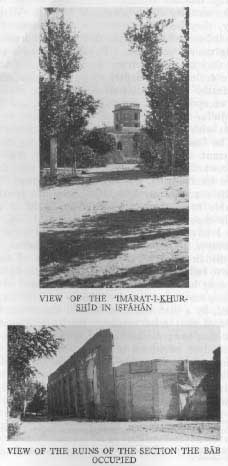

the Mu'tamid, known by the name of

Imarat-i-Khurshid,(2) and was introduced,

through a side entrance reserved

for the Mu'tamid himself, into his private

apartments. The governor waited

in person on the Bab, served His meals,

and provided whatever was required

for His comfort and safety.(3)

remaining hundred should likewise be

ordered by him to return to the city.

Of the twenty remaining horsemen, the

Mu'tamid directed that ten should be

despatched to Ardistan for the purpose

of collecting the taxes levied by the

government, and that the rest, all of

whom should be of his tried and most

reliable men, should, by an unfrequented

route, bring the Bab back in

disguise to Isfahan.(1) They were, moreover,

instructed so to regulate their

march that before dawn of the ensuing

day the Bab should have arrived at

Isfahan and should have been delivered

into his custody. This plan was

immediately taken in hand and duly

executed. At an unsuspected hour the

Bab re-entered the city, was directly

conducted to the private residence of

the Mu'tamid, known by the name of

Imarat-i-Khurshid,(2) and was introduced,

through a side entrance reserved

for the Mu'tamid himself, into his private

apartments. The governor waited

in person on the Bab, served His meals,

and provided whatever was required

for His comfort and safety.(3)

Meanwhile the wildest conjectures obtained currency in

the city regarding the journey of the Bab to Tihran, the sufferings

which He was made to endure on His way to the

capital, the verdict which had been pronounced against Him,

and the penalty which He had suffered. These rumours

greatly distressed the believers who were residing in Isfahan.

The Mu'tamid, who was well aware of their grief and anxiety,

interceded with the Bab in their behalf and begged to be

allowed to introduce them into His presence. The Bab addressed

a few words in His own handwriting to Mulla Abdu'l-Karim-i-Qazvini,

who had taken up his quarters in the

madrisih of Nim-Avard, and instructed the Mu'tamid to

send it to him by a trusted messenger. An hour later, Mulla

Abdu'l-Karim was ushered into the presence of the Bab.

Of his arrival no one except the Mu'tamid was informed.

He received from his Master some of His writings, and was

instructed to transcribe them in collaboration with Siyyid

Husayn-i-Yazdi and Shaykh Hasan-i-Zunuzi. To these he

soon returned, bearing the welcome news of the Bab's well-being

and safety. Of all the believers residing in Isfahan,

these three alone were allowed to see Him.

Meanwhile the wildest conjectures obtained currency in

the city regarding the journey of the Bab to Tihran, the sufferings

which He was made to endure on His way to the

capital, the verdict which had been pronounced against Him,

and the penalty which He had suffered. These rumours

greatly distressed the believers who were residing in Isfahan.

The Mu'tamid, who was well aware of their grief and anxiety,

interceded with the Bab in their behalf and begged to be

allowed to introduce them into His presence. The Bab addressed

a few words in His own handwriting to Mulla Abdu'l-Karim-i-Qazvini,

who had taken up his quarters in the

madrisih of Nim-Avard, and instructed the Mu'tamid to

send it to him by a trusted messenger. An hour later, Mulla

Abdu'l-Karim was ushered into the presence of the Bab.

Of his arrival no one except the Mu'tamid was informed.

He received from his Master some of His writings, and was

instructed to transcribe them in collaboration with Siyyid

Husayn-i-Yazdi and Shaykh Hasan-i-Zunuzi. To these he

soon returned, bearing the welcome news of the Bab's well-being

and safety. Of all the believers residing in Isfahan,

these three alone were allowed to see Him.

One day, while seated with the Bab in his private garden

within the courtyard of his house, the Mu'tamid, taking his

Guest into his confidence, addressed Him in these words:

"The almighty Giver has endowed me with great riches.(1) I

know not how best to use them. Now that I have, by the

aid of God, been led to recognise this Revelation, it is my

ardent desire to consecrate all my possessions to the furtherance

of its interests and the spread of its fame. It is my

intention to proceed, by Your leave, to Tihran, and to do

my best to win to this Cause Muhammad Shah, whose confidence

in me is firm and unshaken. I am certain that he

will eagerly embrace it, and will arise to promote it far and

wide. I will also endeavour to induce the Shah to dismiss

the profligate Haji Mirza Aqasi, the folly of whose administration

has well-nigh brought this land to the verge of ruin.

Next, I will strive to obtain for You the hand of one of the

One day, while seated with the Bab in his private garden

within the courtyard of his house, the Mu'tamid, taking his

Guest into his confidence, addressed Him in these words:

"The almighty Giver has endowed me with great riches.(1) I

know not how best to use them. Now that I have, by the

aid of God, been led to recognise this Revelation, it is my

ardent desire to consecrate all my possessions to the furtherance

of its interests and the spread of its fame. It is my

intention to proceed, by Your leave, to Tihran, and to do

my best to win to this Cause Muhammad Shah, whose confidence

in me is firm and unshaken. I am certain that he

will eagerly embrace it, and will arise to promote it far and

wide. I will also endeavour to induce the Shah to dismiss

the profligate Haji Mirza Aqasi, the folly of whose administration

has well-nigh brought this land to the verge of ruin.

Next, I will strive to obtain for You the hand of one of the

As the days of his earthly life were drawing to a close,

the Mu'tamid increasingly sought the presence of the Bab,

and, in his hours of intimate fellowship with Him, obtained

a deeper realisation of the spirit which animated His Faith.

"As the hour of my departure approaches," he one day told

the Bab, "I feel an undefinable joy pervading my soul. But

I am apprehensive for You, I tremble at the thought of

being compelled to leave You to the mercy of so ruthless a

successor as Gurgin Khan. He will, no doubt, discover

Your presence in this home, and will, I fear, grievously ill-treat

You." "Fear not," remonstrated the Bab; "I have

As the days of his earthly life were drawing to a close,

the Mu'tamid increasingly sought the presence of the Bab,

and, in his hours of intimate fellowship with Him, obtained

a deeper realisation of the spirit which animated His Faith.

"As the hour of my departure approaches," he one day told

the Bab, "I feel an undefinable joy pervading my soul. But

I am apprehensive for You, I tremble at the thought of

being compelled to leave You to the mercy of so ruthless a

successor as Gurgin Khan. He will, no doubt, discover

Your presence in this home, and will, I fear, grievously ill-treat

You." "Fear not," remonstrated the Bab; "I have

As the life of the Mu'tamid was approaching its end, the

Bab summoned to His presence Siyyid Husayn-i-Yazdi and

Mulla Abdu'l-Karim, acquainted them with the nature of

His prediction to His host, and bade them tell the believers

who had gathered in the city, to scatter throughout Kashan,

Qum, and Tihran, and await whatever Providence, in His

wisdom, might choose to decree.

As the life of the Mu'tamid was approaching its end, the

Bab summoned to His presence Siyyid Husayn-i-Yazdi and

Mulla Abdu'l-Karim, acquainted them with the nature of

His prediction to His host, and bade them tell the believers

who had gathered in the city, to scatter throughout Kashan,

Qum, and Tihran, and await whatever Providence, in His

wisdom, might choose to decree.

A few days after the death of the Mu'tamid, a certain

person who was aware of the design which he had conceived

and carried out for the protection of the Bab, informed his

successor, Gurgin Khan,(3) of the actual residence of the Bab

in the Imarat-i-Khurshid, and described to him the honours

which his predecessor had lavished upon his Guest in the

privacy of his own home. On the receipt of this unexpected

intelligence, Gurgin Khan despatched his messenger to

Tihran and instructed him to deliver in person the following

A few days after the death of the Mu'tamid, a certain

person who was aware of the design which he had conceived

and carried out for the protection of the Bab, informed his

successor, Gurgin Khan,(3) of the actual residence of the Bab

in the Imarat-i-Khurshid, and described to him the honours

which his predecessor had lavished upon his Guest in the

privacy of his own home. On the receipt of this unexpected

intelligence, Gurgin Khan despatched his messenger to

Tihran and instructed him to deliver in person the following

The Shah, who was firmly convinced of the loyalty of

the Mu'tamid, realised, when he received this message, that

the late governor's sincere intention had been to await a

favourable occasion when he could arrange a meeting between

him and the Bab, and that his sudden death had interfered

with the execution of that plan. He issued an imperial mandate

summoning the Bab to the capital. In his written

message to Gurgin Khan, the Shah commanded him to send

the Bab in disguise, in the company of a mounted escort(1) headed by Muhammad Big-i-Chaparchi,(2) of the sect of the Aliyu'llahi, to Tihran; to exe

rcise the utmost consideration

towards Him in the course of His journey, and strictly to

maintain the secrecy of His departure.(3)

The Shah, who was firmly convinced of the loyalty of

the Mu'tamid, realised, when he received this message, that

the late governor's sincere intention had been to await a

favourable occasion when he could arrange a meeting between

him and the Bab, and that his sudden death had interfered

with the execution of that plan. He issued an imperial mandate

summoning the Bab to the capital. In his written

message to Gurgin Khan, the Shah commanded him to send

the Bab in disguise, in the company of a mounted escort(1) headed by Muhammad Big-i-Chaparchi,(2) of the sect of the Aliyu'llahi, to Tihran; to exe

rcise the utmost consideration

towards Him in the course of His journey, and strictly to

maintain the secrecy of His departure.(3)

Gurgin Khan went immediately to the Bab and delivered

into His hands the written mandate of the sovereign. He

then summoned Muhammad Big, conveyed to him the behests

of Muhammad Shah, and ordered him to undertake

immediate preparations for the journey. "Beware," he

warned him, "lest anyone discover his identity or suspect

the nature of your mission. No one but you, not even the

members of his escort, should be allowed to recognise him.

Should anyone question you concerning him, say that he is

Gurgin Khan went immediately to the Bab and delivered

into His hands the written mandate of the sovereign. He

then summoned Muhammad Big, conveyed to him the behests

of Muhammad Shah, and ordered him to undertake

immediate preparations for the journey. "Beware," he

warned him, "lest anyone discover his identity or suspect

the nature of your mission. No one but you, not even the

members of his escort, should be allowed to recognise him.

Should anyone question you concerning him, say that he is

|