BAFA © 2010. All material here is copyrighted. See conditions above. |

Yuichi Hirano architect, Japan

|

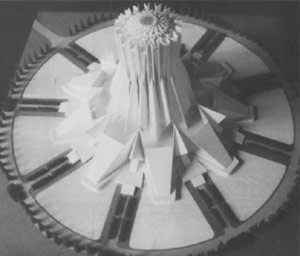

Model for a design for a Bahá'í House

of Worship

in Japan by Yuichi Hirano, Japan.

|

Design for a Bahá'í House of Worship in Japan

by Yuichi Hirano.

As an architect, the idea of designing a Bahá'í House of Worship in Japan has intrigued me ever since I became a Bahá'í. The need for such a building seems very far off into the future, but then, I thought, why not try it anyway.

The design arose purely from my own personal desire to experiment with expressing the principles of Bahá'u'lláh's teachings in this unique architectural medium. At first I didn't want show it to any Bahá'ís because of the danger of misunderstanding.

It is not meant to be a definitive design, but rather a reference point for architects who want to take up the task of designing a House of Worship for Japan.

|

However I was invited to present the design at the 1998 Japanese Association for Bahá'í Studies conference which focussed on the arts. So with trepidation and excitement, I did.

The challenge in creating the design was finding a way to express Japanese spiritual and artistic traditions within the framework of the basic structure usual for Bahá'í Houses of Worship. The seven Houses of Worship that exist today each have their own unique features, but their basic structure remains centripetal. A centralized plan with nine entrances that flow into a single space beneath a central dome, symbolizing unity, a focal concept in the Bahá'í Faith. The use of natural light to illuminate the central hall is another common feature. The issue before me then was how to express something Japanese within this structural context. I was greatly inspired by the process whereby Mr. Sabha discovered the lotus, which he used in his design of the House of Worship in New Delhi to symbolize India's spiritual culture. I began to search for some shape or form that represented Japan's spiritual culture.

In Japan, the development of aesthetic sensitivity is considered to be a means of increasing one's spirituality. The tea ceremony, ikebana (flower arranging) and noh (early formalistic theatre) all seek to achieve spiritual enlightenment through the honing of the individual's aesthetic senses. Similarly, much labour has been expended in both Buddhist and Shinto traditions on creating beautiful statues, temples, shrines and so on. This attention to beauty is also an integral part of daily life. Ordinary Japanese people are very familiar with the aesthetics of Japanese cooking, clothing, gardening, bonsai (miniature tree sculpting) and ikebana. It seemed appropriate therefore to take this concept of beauty and seek a basic form within it, or the aesthetic principles behind it, and to find a means of reflecting that in the House of Worship design.

As a result, I chose two images: the curved line and the folded- plane surface. The former, a slightly curved line, is represented by the silhouette of Mount Fuji and can be found in the stone walls surrounding Japanese castles, the curve of a Japanese sword blade, the slope of shrine and temple roofs, and the outline of the torii (shrine gate). The folded-plane surface is a technique used in Japanese kimono, origami (paper folding), fans, screens, and so on, whereby a complex three-dimensional shape is composed by folding and layering a plane surface.

In order to express these two aspects in the design, I decided on a folded-plate structure of reinforced concrete. The House of Worship is surrounded by eighteen almost vertical folded- plates, which support the central dome. Glass panels fill the spaces between each of the eighteen independent plates, allowing natural light to flood the interior. The most difficult task was determining how to incorporate a centralized plan. In Japanese traditional architecture, there are very few examples of the central hall, which characterizes the Bahá'í Houses of Worship, and there are no domes at all. There are several polygonal halls in the style of Yumedono at Horyuji temple, but none of them is capped by a dome. In this design, therefore, the surrounding plates extend to the top of the dome, making it less conspicuous from the outside. Structural issues and the problem of durability have not been addressed, and it is very likely that the structure could not be built as designed, but I hope that it will inspire the Bahá'ís with a vision of possibilities. I also hope to have the opportunity to use what I have learned to develop another design in future.

Arts Dialogue, June 2002, page 21.

|

Arts Dialogue, Dintel 20, NL 7333 MC, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands

email: bafa@bahai-library.com

|

|