| Music | U.S.A. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

BAFA © 2010. All material here is copyrighted. See conditions above. |

Dizzy Gillespie

Jazz Trumpet, U.S.A.

|

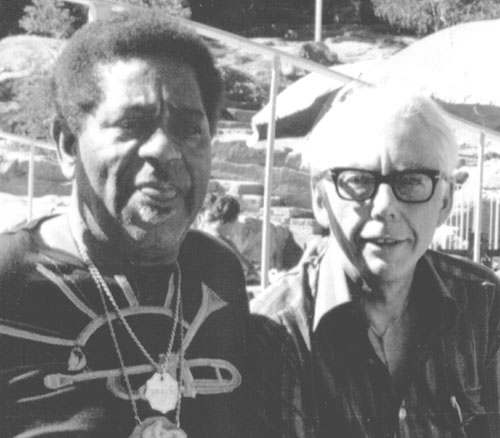

Dizzy Gillespie and Lowell Johnson, in Maseru, Lesotho in December 1977.

|

Compiled by Sen McGlinn

On January 6th Jazz Trumpet player 'Dizzy' (John Birks) Gillespie died in New Jersey, U.S.A. at the ripe old age of 75.

|

|

So popular did he become that at election-time in America T-shirts appeared with his portrait and the words "Dizzy for President".

|

Chris Ruhe performing with Dizzy Gillespie in 1991 in Chile.

|

|

Dizzy a poem by June Perkins was part of the artwork, Conversations by Sonja van Kerkhoff, on show in a music shop in Leiden as part of the Close to the Wall Poetry festival, 2005.  June Perkins' 57 line poem, also published in the book, Just Let the Wind was displayed along the whole wall of this shop for 2 months in the summer of 2005.

June Perkins' 57 line poem, also published in the book, Just Let the Wind was displayed along the whole wall of this shop for 2 months in the summer of 2005. The drawings by Sonja van Kerkhoff on transparent film on the mirrored walls, became more or less visible as you walked past. The images and broken images were intended to create their own voices or 'musics' in reaction to the words, sounds and rhythms in the poem, to jam along like one long score of music.

The drawings by Sonja van Kerkhoff on transparent film on the mirrored walls, became more or less visible as you walked past. The images and broken images were intended to create their own voices or 'musics' in reaction to the words, sounds and rhythms in the poem, to jam along like one long score of music.

|

I said yes, and the young man said: "I just came to warn you. Dizzy Gillespie is looking for you. He wants to punch you back to Johannesburg."

|

|

He had caught my accent. It was the first time in my life that I had ever been grateful to be an American. I hastily proceeded to take advantage of the hesitation. "Yes, I am an American. I have been a disc-jockey in South Africa since 1953. Most of my listeners are from Soweto and townships like Mamelodi, and they would be very happy to have a word of greetings from Dizzy Gillespie." He hesitated, relaxed his fist and shoulders, and after a struggle, he lowered his arm, but said, "No, not for South Africa." Of course Dizzy's attitude towards apartheid and South Africa is well-known... He returned and crossed to the tables on the other side of the lawn abandoning our table completely. ...In 1968 when Martin Luther King was assassinated Dizzy was deeply disturbed. The civil rights were important to him as were King's spiritual principles. Dizzy had already heard of the teachings of Bahá'u'lláh from a book a fan gave him but he had paid little attention. However with his friend Martin Luther King being killed so tragically Dizzy needed consolation. He began a Bahá´í in 1968 and recorded his reasons in his 1979 biography, "To Be, or Not ... to Bop". "...Becoming a Bahá´í changed my life in every way and gave me a new concept of relationship between man and his fellow-men and his family. I became more spiritually aware, and when you are more spiritually aware that will be reflected in what you do." Dizzy was never into drugs because he saw what they did to Charlie Parker and some of his other friends. Dizzy even gave up alcohol. When challenged he would just say: "It's a Bahá´í law. And it is good for me." And change the subject. The next time I had a chance to meet Dizzy, except at clubs in New York, was at his concert in Lesotho in December 1977... Remembering the 1963 fiasco, I decided to try my luck at getting a personal interview with him again. So I rang his room from the hotel lobby and said: "My name is Lowell Johnson, a South African dee-jay and the secretary of the National Bahá´í Assembly of South Africa..." "Sure, come on up." So I went to his room, knocked, and he greeted me with just a towel - he was just out of the shower. The very first thing he wanted to know was how the Bahá´í Faith was progressing, and how it was introduced into South Africa. I told him some humourous stories... of our times in Cape Town meeting Nyanga and Langa people behind the high walls and high hedges in order not to offend the neighbours; the need for caution and the wonder of Africans when they experienced equality at the table in a white home... Dizzy was not amused. Even in telling him of my times in Johannesburg in the early sixties, of how I had opportunity to explain the Bahá´í principles to the police. There was no smile and no comment from Dizzy. His position was clear. But we had a wonderful few days together and he asked me to chair his "soiree" at midnight for those who wanted to hear about the Bahá´í Faith. It was beautiful to see how he explained that the Bahá´í have no race prejudice. He kept repeating his favourite quotation: "The earth is but one country and mankind its citizens". ...After that I and other Bahá´ís tried to get him to South Africa, but Bill Sears told me, he always said: "It is not necessary; the Bahá´ís in South Africa are taking good care of that country." He meant, of course, promoting the oneness of humankind. Dizzy was a thorough professional. From Bahá´í friends I have learned that he often attended and visited Bahá´í homes all over the world. His world travels as humanity's jazz ambassador are legendary. Three hours before any concert he would always excuse himself, regardless of many efforts to persuade him to stay longer. He insisted that he always needed two hours to warm up... My latest opportunity to see Dizzy was on November 26, 1992 at Carnegie Hall in New York. I was in New York for the second Bahá´í world congress and it was Dizzy's 75th birthday concert and his offering to the celebration of the centenary of the passing of Bahá'u'lláh. Dizzy was to appear there at Carnegie Hall for the 33rd time. The line-up read impressively like a who's who of jazz: Dizzy, John Faddis, "Doc" Holliday, James Moody, Paquito D'Rivera, and the Mike Longo Trio with Ben Brown on bass and Mickey Rocker on drums. But Dizzy didn't make it because he was in bed suffering from cancer of the pancreas. But the musicians played their hearts out for him, no doubt suspecting that he would not play again. Each musician gave tribute to their friend, this great soul and innovator in the world of jazz... There was one more Bahá´í who had a great influence on Dizzy. He met Enoch Olinga in Nairobi and they clicked instantly... Enoch gave Dizzy some African shirts and encouraged his search for his African roots. When Enoch was murdered in 1979 for no apparent reason, Dizzy felt bereft. He consoled himself by composing "Olinga". It became part of his repertoire and Milt Jackson recorded it with Mickey Roker, Dizzy's drummer. Dizzy had two funerals. One was a Bahá´í funeral at his request, at which his closest friends and colleagues attended. The second was at a Lutheran church in New York attended by the world. Excerpts from an article printed in the Tribute, South Africa March 1993 Excerpts from the BAFA newsletter, December 1993, page 7. |

|

Arts Dialogue, Dintel 20, NL 7333 MC, Apeldoorn, The Netherlands email: bafa@bahai-library.com |